Cantonese opera

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

| Cantonese opera | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is part of the series on |

| Cantonese culture |

|---|

Cantonese opera is one of the major categories in Chinese opera, originating in southern China's Guangdong Province. It is popular in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, Macau and among Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. Like all versions of Chinese opera, it is a traditional Chinese art form, involving music, singing, martial arts, acrobatics, and acting.

History

[edit]There is debate about the origins of Cantonese opera, but it is generally accepted that opera was brought from the northern part of China and slowly migrated to the southern province of Guangdong in the late 13th century, during the late Southern Song dynasty. In the 12th century, there was a theatrical form called the Nanxi or "Southern drama", which was performed in public theatres of Hangzhou, then capital of the Southern Song. With the invasion of the Mongol army, Emperor Gong of the Song dynasty fled with hundreds of thousands of Song people into Guangdong in 1276. Among them were Nanxi performers from Zhejiang, who brought Nanxi into Guangdong and helped develop the opera traditions in the south.

Many well-known operas performed today, such as Tai Nui Fa originated in the Ming Dynasty and The Purple Hairpin originated in the Yuan Dynasty, with lyrics and scripts in Cantonese. Until the 20th century all the female roles were performed by males.

Early development in Shanghai

[edit]In the 1840s, a large number of Guangdong businessmen came to Shanghai for opportunities. They owned abundant resources, therefore, their influence in Shanghai has gradually increased (Song, 1994).[1] Later, various clansmen associations have been established to sponsor different cultural activities, Cantonese opera was one of them. From the 1920s to the 1930s, the development of Cantonese opera in Shanghai was very impressive (Chong, 2014).[2] At that time, the department stores opened by the Cantonese businessmen in Shanghai had their Cantonese opera theater companies.[3] Moreover, the Guangdong literati in Shanghai always put great effort into promotions of Guangdong opera. A newspaper recorded that "The Cantonese operas were frequently played at that time. And the actors who came to perform in Shanghai were very famous. Every time many Cantonese merchants made reservations for inviting their guests to enjoy the opera".(Cheng, 2007)[4]

Development in Hong Kong

[edit]Beginning in the 1950s immigrants fled Shanghai to areas such as North Point.[5] Their arrival significantly boosted the Cantonese opera fan-base. Also, the Chinese Government wanted to deliver the message of socialist revolution to Chinese people under colonial governance in Hong Kong.[6] Agents of the Chinese government founded newspaper platforms, such as Ta Kung Pao (大公報) and Chang Cheung Hua Pao (長城畫報) to promote Cantonese Opera to the Hong Kong audience. These new platforms were used to promote new Cantonese Opera releases. This helped to boost the popularity of Cantonese Opera among the Hong Kong audience. Gradually, Cantonese Opera became a part of daily entertainment activity in the colony.

The popularity of a Cantonese Opera continued to grow during the 1960s.[7] More theatres were established in Sheung Wan and Sai Wan, which became important entertainment districts. Later, performances began to be held in playgrounds, which provided more opportunities to develop Cantonese Opera in Hong Kong. As the variety of venues grew, so the variety of audiences became wider. However, Cantonese Opera began to decline as TV and cinema started to develop in the late 1960s. Compared to Cantonese Opera, cinema was cheaper and TV was more convenient. Subsequently, some theatres started to be repurposed as commercial or residential buildings. The resulting decline in available theatres further contributed to the decline of Cantonese Opera in the territory.

Since the demolition of Lee Theatre and the closing down of many stages (Tai Ping Theatre, Ko Shing Theatre, Paladium Theatre, Astor Theatre or former Po Hing Theatre, Kai Tak Amusement Park and Lai Chi Kok Amusement Park) that were dedicated to Cantonese genre throughout the decades, Hong Kong's Sunbeam Theatre is one of the last facilities that is still standing to exhibit Cantonese Opera.

By the early 1980s, Leung Hon-wai was one of the first in his generation of the Chinese Artists Association of Hong Kong (hkbarwo) who gave classes and actively engaged in talent-hunting. The Cantonese Opera Academy of Hong Kong classes started in 1980.

To intensify education in Cantonese opera, they started to run an evening part-time certificate course in Cantonese Opera training with assistance from The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts in 1998. In 1999, the Association and the Academy further conducted a two-year daytime diploma programme in performing arts in Cantonese Opera in order to train professional actors and actresses. Aiming at further raising the students' level, the Association and the Academy launched an advanced course in Cantonese opera in the next academic year.

In recent years, the Hong Kong Arts Development Council has given grants to the Love and Faith Cantonese Opera Laboratory to conduct Cantonese opera classes for children and young people. The Leisure and Cultural Services Department has also funded the International Association of Theatre Critics (Hong Kong Branch) to implement the "Cultural Envoy Scheme for Cantonese Opera" for promoting traditional Chinese productions in the community.

Also, the Hong Kong Government planned to promote Cantonese Opera through different communication channels.[8] They wanted to build more theatres for the Hong Kong public to have more opportunities to enjoy Cantonese Opera. The scheme also arrived to develop professional talents in Cantonese Opera. Cantonese Opera became a part of the compulsory Music subject in primary school. For teachers, the Education Bureau provided some training and teaching materials related to Cantonese Opera.

Art festivals

[edit]In the first decade of the Hong Kong Arts Festivals and the Festivals of Asian Arts, Cantonese opera performances contributed by those representing the lion share of the market, (well-established troupes, well-known performers Lang Chi Bak as well as Leung Sing Poh in their golden years or prominent performers in their prime) are:-

Fung Wong-nui (1925–1992)

- 1974, 2nd Hong Kong Arts Festival (self-financing 3 titles)

- 《薛平貴》Xue Pinggui

- 《胡不歸》Time To Go Home

- 《貍貓換太⼦》Substituting a Racoon for the Prince

- 1979, 7th Hong Kong Arts Festival*

- 1980, 8th Hong Kong Arts Festival

Lam Kar Sing[9] (1933–2015), bearer of the tradition handed down by Sit Gok Sin and owner of name brand/tradition (personal art over lucrative "for hire" careers in films or on stage) as well as volunteer tutor to two ([10] 1987, 2008[11]) students[12] handpicked right out of training schools

- 1976, 1st Festival of Asian Arts

- 1977, 2nd Festival of Asian Arts

- 1978, 6th Hong Kong Arts Festival*

- 《梁祝恨史》Butterfly Lovers

- Yam-Fong title

- For two decades a regular if opposite Lee Bo-ying

- Loong Kim Sang lost the only compatible co-star for this title in 1976

- One of many traceable artistic interpretations of same legend

- Lam forged his own (still opposite Lee Bo-ying) in November 1987 and made that the contemporary prevailing version

- 《梁祝恨史》Butterfly Lovers

- 1978, 3rd Festival of Asian Arts

- 1980, 5th Festival of Asian Arts

- 1982, 7th Festival of Asian Arts

- 1984, Chinese Opera Fortnight (中國戲曲匯演)

- 《胡不歸》Time To Go Home – the contemporary prevailing version[15]

- 《雷鳴金鼓戰笳聲》The Sounds of Battle

- 《三夕恩情廿載仇》Romance and Hatred

- 《無情寶劍有情天》Merciless Sword Under Merciful Heaven

- Last time both Lang Chi Bak (1904-1992)and Leung Sing Poh performed was in 1979.

- 1983, 8th Festival of Asian Arts

- 1984, 9th Festival of Asian Arts

- 《帝女花》Di Nü Hua

- 《紫釵記》The Purple Hairpin

- 《紅樓夢》Dream of Red Chamber

- 40 years since Yam's best known role and title (opposite Chan Yim Nung) in 1944

- New script debuted in November 1983

- Contemporary prevailing version

- 《花田八喜》Mistake at the Flower Festival

- 《再世紅梅記》The Reincarnation of a Beauty

- 《牡丹亭驚夢》The Peony Pavilion

- 1985, 10th Festival of Asian Arts

Obscure groups of experimental nature, let alone those late boomers without market value, were not on the map or in the mind of those organizing these events. That changed since the 40 something Leung Hon-wai found his way to the stepping stone or launching pad he desired for pet projects of various nature.

Public funding

[edit]This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as mostly incomprehensible, see talk page. (July 2024) |

To continue the tradition by passing on what elders and veterans inherited from former generations and to improve sustainability with new and original music, lyrics and scripts.

- Cantonese Opera Development Fund[16]

- Hong Kong Arts Development Council, Grants[17]

Heritage is as abstract a concept as traditions is while monetary support is real. However, elders are not ombudspersons in any sense and they take public funds for their own reasons. That is, they are knee deep in commercial performances even as a member of the above organizations.

A juren a century ago can be an adjunct associate professor now in Hong Kong. How business was conducted in a community by a juren was illustrated by Ma Sze Tsang in a film called the Big Thunderstorm (1954).

Trend-setting figure, Leung Hon-wai, talked on camera about his doctrine related to new titles he wrote and monetary backings from the various Hong Kong authorities. That is, art festivals provided him financial means, identity, advertising resources and opportunities not otherwise available. Curious audience makes good box-office for the only 2–3 shows of a single new title. In addition, he only paid 50% to collect the new costumes in his possession for future performances of different titles.

A Sit Kok Sin classic fetched HK$105,200 plus in 2015. The parents who had over 100 years of experience combined found sharing the stage with their son as not feasible without subsidies for Golden Will Chinese Opera Association and Wan Fai-yin, Christina.

Time To Go Home is different from those Leung debuted at arts festivals since:-

- This 1939 Sit classic has been a rite of passage for new performers to become prominent male leads.

- It only involves minimum costumes, props and crew size.

- It is popular as afternoon fillers by third tier performers in bamboo theaters.

In 2019, Yuen Siu Fai talked on radio that he found the readily available funding made beneficiaries financially irresponsible, unlike himself and others who put their own money where their mouths were. Yuen, who works regularly for troupes with secure public funding, did not draw a link between his two roles.

Contrary to Africa, the entire village is responsible for raising the children of a certain crowd only. Both political and social guanxi is making or breaking the future of up-and-coming performers in the same way as whether Bak Yuk Tong is remembered as one of the Four Super Stars or not. According to Yuen, Bak is anti-communist and therefore his status is different in Mainland China (PRC).

Private funding

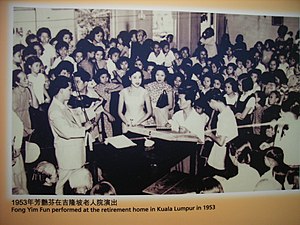

[edit]- The Art of Fong Yim-fun Sustainability Project, Shaw College, CUHK.

In August 2014, the Fong Yim Fun Art Gallery was formally opened.[18] - Dr. Yang Leung Yin-fong Katie, the Honorary Life Chairman, donated one of her properties to be the permanent office of the Chinese Artists Association of Hong Kong to provide residences for aged musicians.

In 2019, Yuen Siu Fai said that old performers are to stay front and center on stage as long as they want to take center stage instead of sharing, let alone ceding, the limelight to the next or even younger generations. Yuen insists that performers without bags under their eyes could not be any good.

In 2018, Law Kar Ying said Chan Kam Tong had already jumped the shark in the mid-1950s, more than ten years before Chan actually left the stage or more than 60 years for it to be confirmed to the public. The (Yuen, Law and others) generation with bags under their eyes picked up where Leung left off. By such, these old performers are upholding the Chan tradition and making up records along the way. However, the Chan caliber of masters needed no directors.

Two performers Chan worked with closely, who definitely left the stage at will with dignity, are Yam Kim Fai and Fong Yim Fun. They both openly rebuked (in 1969 and in 1987 respectively in no harsher way than what Lam Kar Sing and his wife did in 1983) individual off-springs who were under their wings briefly but officially. The popularity of Yam-Fong in Hong Kong continues to thrive notwithstanding their apparent lack of official successors as Loong Kim Sang and Lee Bo Ying picked up where they left off.

Cantonese opera in Hong Kong rocketed around 1985/86, according to Li Jian, born Lai Po Yu, (黎鍵,原名黎保裕), an observer. De facto successors to master performers, Lee Bo Ying, Lam Kar Sing, and Loong Kim Sang all left the stage in or before 1993, last watershed moment of Cantonese opera for Hong Kong and beyond in the 20th century. The consequences are also significant and long lasting. Unlike Fong and Loong, Yam and Lee never returned.

For the rest of her life, Yam didn't even take the bow at curtain calls although she was in the audience on most days that Loong's troupe performed in Hong Kong. Comfortable enough around Yam, Yuen called Yam lazy because she did not comment on some cake served backstage in those days.

All for naught

[edit]Local Teochew opera troupes lost their ground regarding live-on-stage Ghost Festival opera performances when the business environment was destroyed. Since then, the Teochew category disappeared in Hong Kong.

Chan Kim-seng, the former chairperson of Chinese Artists Association of Hong Kong, saw similar threats towards Cantonese opera and fought tooth and nail for job security of members. Chan, Representative Inheritor of Cantonese opera in the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, passed away on 19 August 2013.[19]

Characteristics

[edit]Cantonese opera shares many common characteristics with other Chinese theatre genres. Commentators often take pride in the idea that all Chinese theatre styles are similar but with minor variations on the pan-Chinese music-theatre tradition and the basic features or principles are consistent from one local performance form to another. Thus, music, singing, martial arts, acrobatics and acting are all featured in Cantonese opera. Most of the plots are based on Chinese history and famous Chinese classics and myths. Also, the culture and philosophies of the Chinese people can be seen in the plays. Virtues (like loyalty, love, patriotism and faithfulness) are often reflected by the operas.

Some particular features of Cantonese opera are:

- Cing sik sing (程式性; Jyutping: cing4 sik1 sing3) – formulaic, formalised.

- Heoi ji sing (虛擬性; Jyutping: heoi1 ji5 sing3) – abstraction of reality, distancing from reality.

- Sin ming sing (鮮明性; Jyutping: sin1 ming4 sing3) – clear-cut, distinct, unambiguous, well-defined.

- Zung hap ngai seot jing sik (綜合藝術形式; Jyutping: zung3 hap6 ngai6 seot6 jing4 sik1) – a composite or synthetic art form.

- Sei gung ng faat (四功五法; Pinyin: sì gōng wǔ fǎ, Jyutping: sei3 gung1 ng5 faat3) – the four skills and the five methods.

The four skills and five methods are a simple codification of training areas that theatre performers must master and a metaphor for the most well-rounded and thoroughly-trained performers. The four skills apply to the whole spectrum of vocal and dramatic training: singing, acting/movements, speech delivery, and martial/gymnastic skills; while the five methods are categories of techniques associated with specific body parts: hands, eyes, body, hair, and feet/walking techniques.

The acting, acrobat, music and singing, live on stage, are well known as essential characteristics of live performances in theaters. Recordings did not replace the human voice backstage behind prop only when choir members were actually introduced to the audience at curtain call.

Significance

[edit]

Before widespread formal education, Cantonese opera taught morals and messages to its audiences rather than being solely entertainment. The government used theatre to promote the idea of be loyal to the emperor and love the country (忠君愛國). Thus, the government examined the theatre frequently and would ban any theatre if a harmful message was conveyed or considered. The research conducted by Lo showed that Cantonese Operatic Singing also relates older people to a sense of collectivism, thereby contributing to the maintenance of interpersonal relationships and promoting successful ageing. (Lo, 2014).[20] Young people construct the rituals of learning Cantonese opera as an important context for their personal development.[21]

Operas of Deities

[edit]Cantonese opera is a kind of Operas of Deities. Operas for Deities are often performed in celebration of folk festivals, birthdays of deities, establishments or renovations of altars and temples.[22] A community organises a performance of opera, which is used to celebrate the birth of the gods or to cooperate with the martial arts activities, such as "Entertaining People and Entertaining God" and "God and People". These performances can be called " Operas for Deities ". This king of acting originated from the Ming Dynasty and the Qing Dynasty. It was also called the sacred drama in the performance of God's birthday. It is a meritorious deed for God.[23] According to the study, most of the Cantonese operas in Hong Kong belong to the Operas for Deities, and the nature of the preparations of the "God Circus" can be broadly divided into three categories: the celebration of the gods, the Hungry Ghost Festival, the Taiping Qing Dynasty, the temple opening and the traditional festival celebrations.[24] In the 1960s−1970s, the Chinese opera was at a low ebb. However, due to the support of Opera for Deities, some of the troupes can be continue to perform. In the 1990s, the total performance rate of Operas for Deities has been reduced from two-thirds to two-fifths in the 1980s, there is no such thing as a performance in the Cantonese opera industry.[25]

Performers and roles

[edit]Types of play

[edit]There are two types of Cantonese opera plays: Mou (武, "martial arts") and Man (文, "highly educated", esp. in poetry and culture). Mou plays emphasize war, the characters usually being generals or warriors. These works contain action scenes and involve a lot of weaponry and armour. Man plays tend to be gentler and more elegant. Scholars are the main characters in these plays. Water sleeves are used extensively in man plays to produce movements reflecting the elegance and tenderness of the characters; all female characters wear them. In man plays, characters put a lot of effort into creating distinctive facial expressions and gestures to express their underlying emotions.

Roles

[edit]There are four types of roles: Sang (Sheng), Daan (Dan), Zing (Jing), and Cau (Chou).

Sang

[edit]The Sang (生; Sheng) are male roles. As in other Chinese operas, there are different types of male roles, such as:

- Siu2 Sang1 (小生) – Literally, young gentleman, this role is known as a young scholar.

- Mou5 Sang1 (武生) – Male warrior role.

- Siu2 Mou5 Sang1 (小武生) – Young Warrior (usually not lead actor but a more acrobatic role).

- Man4 Mou5 Sang1 (文武生) – Literally, civilized martial man, this role is known as a clean-shaven scholar-warrior. Actresses for close to a century, of three generations and with huge successes worldwide, usually perform this male role are Yam Kim Fai (mentor and first generation), Loong Kim Sang (protégée and second generation), Koi Ming Fai and Lau Wai Ming (the two youngest listed below both by age and by experience).

- Lou5 Sang1 (老生) – Old man role.

- Sou1 Sang1 (鬚生) – Bearded role

Daan

[edit]The Daan (旦; Dan) are female roles. The different forms of female characters are:

- Faa1 Daan2 (花旦) – Literally 'flower' of the ball, this role is known as a young belle.

- Ji6 Faa1 Daan2 (二花旦) – Literally, second flower, this role is known as a supporting female.

- Mou5 Daan2 (武旦) – Female warrior role.

- Dou1 Maa5 Daan2 (刀馬旦) – Young woman warrior role.

- Gwai1 Mun4 Daan2 (閨門旦) – Virtuous lady role.

- Lou5 Daan2 (老旦) – Old woman role.

Zing

[edit]The Zing (淨; Jing) are known for painted-faces. They are often male characters such as heroes, generals, villains, gods, or demons. Painted-faces are usually:

- Man4 Zing2 (文淨) – Painted-face character that emphasizes singing.

- Mou5 Zing2 (武淨) – Painted-face character that emphasizes martial arts.

Some characters with painted-faces are:

- Zhang Fei (張飛; Zœng1 Fei1) and Wei Yan (魏延; Ngai6 Jin4) from Three Humiliations of Zhou Yu (三氣周瑜; Saam1 Hei3 Zau1 Jyu4).

- Xiang Yu (項羽; Hong6 Jyu5) from The Hegemon-King Bids His Concubine Farewell (霸王別姬; Baa3 Wong4 Bit6 Gei1).

- Sun Wukong (孫悟空; Syun1 Ng6 Hung1) and Sha Wujing (沙悟凈; Saa1 Ng6 Zing6) from Journey to the West (西遊記; Sai1 Jau4 Gei3).

Cau

[edit]The Cau (丑; Chou) are clownish figures. Some examples are:

- Cau2 Sang1 (丑生) – Male clown.

- Cau2 Daan2 (丑旦) – Female clown.

- Man4 Cau2 (文丑) – Clownish civilized male.

- Coi2 Daan2 (彩旦) – Older female clown.

- Mou5 Cau2 (武丑) – Acrobatic comedic role.

Notable people

[edit]Major Cantonese Opera artists

[edit]Major Cantonese Opera (Stage) Career Artists[26] include:

| English Name | Chinese | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bak Sheut Sin | 白雪仙 | |

| Wong Chin Sui[citation needed] | 黃千歲 | HKMDB |

| Mak Bing-wing | 麥炳榮 | [citation needed][27][28] |

| Sun Ma Sze Tsang | 新馬師曾 | |

| Kwan Tak Hing | 關德興 | |

| Luo Pinchao | 羅品超 | |

| Chan Kam-Tong | 陳錦棠(武狀元) | [citation needed][29] |

| Yam Bing-yee | 任冰兒[30] (二幫王) |

[31] |

| Lee Heung Kam | 李香琴 | |

| Lam Kar Sing | 林家聲(薛腔) | [32] |

| Ho Fei Fan[citation needed] | 何非凡(凡腔) | [33] |

| Tang Bik-wan | 鄧碧雲(萬能旦后) | |

| Leung Sing Poh | 梁醒波(丑生王) | |

| Lang Chi Bak[34][citation needed] | 靚次伯(武生王) | [35] |

| Tam Lan-Hing | 譚蘭卿(丑旦) | [citation needed][36] |

| Au Yeung Kim[citation needed] | 歐陽儉 | [37] |

- Kai Tak Amusement Park nurtured generation.[clarification needed]

Political-economic crisis led to overall very hard time for Cantonese Opera in Hong Kong. Early 1960s, a sole proprietor in private sector built and operated this facility to provide performance venue, similar (in purpose) to the current Yau Ma Tei Theatre, in which upcoming artists could attain stage experience. Volunteers who managed this Amusement Park Theatre were veteran performer Chan Kam Tong with his wife and others. Work opportunities and incomes nurtured these young promising performers for years.

| English Name | Chinese | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Man Chin Sui* | 文千歲 | |

| Yuen Siu Fai* | 阮兆輝 | [38] |

| Wong Chiu Kwan* | 王超群 | [39] |

| Yan Fei Yin* | 尹飛燕 | [40] |

| Ng May Ying* | 吴美英 | [41][42] |

| Nan Feng* | 南凤 | [43] |

| Law Kar-ying* | 羅家英 | [44] |

| Leung Hon-wai* | 梁漢威 |

The Female Leads

[edit]This is a list of female Cantonese opera performers who are known for female leads (Chinese: 文武全才旦后):

| Actress Name | Chinese | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fung Wong-Nui | 鳳凰女 | Started performing Cantonese opera at age 13.[45][46] |

| Law Yim-hing | 羅艷卿 | Started training on Cantonese opera at age 10.[46] |

| Yu Lai-Zhen | 余麗珍 | Started performing Cantonese opera at age 16. |

| Ng Kwun Lai | 吳君麗 | [46][47] |

| Chan Ho-Kau | 陳好逑 | [46] |

| Chan Yim Nung | 陳艷儂 | [citation needed][48][49][50] |

Female Vocal Styles

[edit]This is a list of female Cantonese opera performers who are known for her own female vocal styles (著名旦腔):

| Actress Name | Chinese | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sheung Hoi-Mui | 上海妹(妹腔) | [citation needed]HKMDB |

| Lee Suet-Fong | 李雪芳(祭塔腔) | [citation needed]HKMDB [51] |

| Hung Sin Nui | 紅線女(紅腔) | |

| Fong Yim Fun | 芳艷芬(芳腔) | Fong-style or the Fong tone.[52][53][54] HKMDB |

| Lee Bo-Ying | 李寶瑩(芳腔) | [55][citation needed]HKMDB |

The Male Leads

[edit]This is a list of female Cantonese opera performers who are known worldwide for singing and performing as male leads. They each has or had spent decades on stage, managed own troupe and established own repertoire as career performers.(著名女文武生): [56]

| Actress Name | Chinese | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Yam Kim Fai | 任劍輝(任腔) | Last on stage in 1969.(40 years) |

| Loong Kim Sang | 龍劍笙(任腔) | First time on stage in 1961.(60 years) |

| Koi Ming Fai | 蓋鳴暉 | Finished training in 1980s. (30 years) |

| Lau Wai Ming | 劉惠鳴 | Finished training in 1980s. (30 years) |

| Cecelia Lee Fung-Sing | 李鳳聲 | Not notable[57][58][59] |

Great Male Vocals

[edit]This is a list of female Cantonese opera singers who are known as Four Great Male Vocals (平喉四大天王):

| Actress Name | Chinese | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tsuih Lau Seen | 徐柳仙(仙腔) | [60]HKMDB |

| Siu Meng Sing | 小明星(星腔) | [60][citation needed]HKMDB |

| Cheung Yuet Yee | 張月兒 | [60] HKMDB |

| Cheung Waih Fong | 張惠芳 | [60] |

Four Super Stars

[edit]This is a list of male Cantonese opera performers who are known as Four Super Stars (四大天王):

| Actor Name | Chinese |

|---|---|

| Sit Gok Sin[citation needed] | 薛覺先(薛腔)[61] |

| Ma Sze Tsang[citation needed] | 馬師曾[62] |

| Kwai Ming Yeung[citation needed] | 桂名揚[63][64] |

| Bak Yuk Tong[citation needed] | 白玉堂[65] |

Four Super Clowns

[edit]This is a list of male Cantonese opera performers who are known as Four Super Clowns (Cau) (四大名丑):

| Actor Name | Chinese |

|---|---|

| Boon Yat On[citation needed] | 半日安[66] |

| Lee Hoi-Chuen | 李海泉 |

| Liu Hap Wai[citation needed] | 廖俠懷[67] |

| Ye Funuo[citation needed] | 葉弗弱[68] |

Visual elements

[edit]Makeup

[edit]

Applying makeup for Cantonese opera is a long and specialized process. One of the most common styles is the "white and red face": an application of white foundation and a red color around the eyes that fades down to the bottom of cheeks. The eyebrows are black and sometimes elongated. Usually, female characters have thinner eyebrows than males. There is black makeup around the eyes with a shape similar to the eyes of a Chinese phoenix (鳳眼; fung6 ngaan5). Lipstick is usually bright red (口唇膏; hau2 seon4 gou1).

A female-role actress is in the processes of applying her markup: spreading a creamy. foundation on her cheeks and forehead; putting blusher on her cheeks, eyelids and both sides of the nose; darling her eyebrows and drawing eye-lines and eye-shadows; pasting hairpieces around her face to create an oval-shaped look; lipstick has been put on prior to this; placing hairpins on the hairpiece.[69]

Actors are given temporary facelifts by holding the skin up with a ribbon on the back of the head. This lifts the corners of the eyes, producing an authoritative look.

Each role has its own style of make-up: the clown has a large white spot in the middle of his face, for example. A sick character has a thin red line pointing upwards in between his eyebrows. Aggressive and frustrated character roles often have an arrow shape fading into the forehead in between the eyebrows (英雄脂; jing1 hung4 zi1).

Strong male characters wear "open face" (開面; hoi1 min4) makeup. Each character's makeup has its own distinct characteristics, with symbolic patterns and coloration.

Costumes

[edit]

Costumes correspond to the theme of the play and indicate the character being portrayed. Costumes also indicate the status of the characters. Lower-status characters, such as females, wear less elaborate dresses, while those of higher rank have more decorative costumes.

Prominent performers (大老倌) listed above, playing the six main characters (generally a combination of 2 Sang, 2 Daan, Zing, and Cau), are usually supposed to pay for their own costumes. Over time, these performers would reinvest their income into their wardrobe which would give an indication of their success. A performer's wardrobe would be either sold or passed on to another performer upon retirement.

To career performers, sequin costumes are essential for festive performances at various "Bamboo Theatres" (神功戲).[70] These costumes, passed from generation to generation of career performers, are priceless according to some art collectors. With time, the materials used for the costumes changed. From the 1950s to the 1960s, sequins were the most prevalent material used for designing the costumes. Nowadays, designers tends to use rhinestones or foil fabric (閃布). Compared to sequins, rhinestones and foil fabric are lighter. However, many older generation performers continue to use sequins and they regard them as more eye-catching on stage.[71]

Most of the costumes in Cantonese Opera come from traditional design. Since costume design is largely taught through apprenticeships, costume design remains largely constant. Some designers are taught the skill from family members, inheriting a particular style.[72]

In 1973, Yam Kim Fai gave Loong Kim Sang, her protégée, the complete set of sequin costumes needed for career debut leading her own commercial performance at Chinese New Year Bamboo Theatre.[73][74]

Some costumes from famous performers, such as Lam Kar Sing[32] and Ng Kwun-Lai,[47] are on loan or donation to the Hong Kong Heritage Museum.

Hairstyle, hats, and helmets

[edit]

Hats and helmets signify social status, age and capability: scholars and officials wear black hats with wings on either side; generals wear helmets with pheasants' tail feathers; soldiers wear ordinary hats, and kings wear crowns. Queens or princesses have jeweled helmets. If a hat or helmet is removed, this indicates the character is exhausted, frustrated, or ready to surrender.

Hairstyles can express a character's emotions: warriors express their sadness at losing a battle by swinging their ponytails. For the female roles, buns indicated a maiden, while a married woman has a 'dai tau' (Chinese: 低頭).

In the Three Kingdoms legends, Zhao Yun and especially Lü Bu are very frequently depicted wearing helmets with pheasants' tail feathers; this originates with Cantonese opera, not with the military costumes of their era, although it's a convention that was in place by the Qing Dynasty or earlier.

Aural elements

[edit]Speech types

[edit]Commentators draw an essential distinction between sung and spoken text, although the boundary is a troublesome one. Speech-types are of a wide variety: one is nearly identical to standard conversational Cantonese, while another is a very smooth and refined delivery of a passage of poetry; some have one form or another of instrumental accompaniment while others have none; and some serve fairly specific functions, while others are more widely adaptable to variety of dramatic needs.

Cantonese opera uses Mandarin or Guān Huà (Cantonese: Gun1 Waa6/2) when actors are involved with government, monarchy, or military. It also obscures words that are taboo or profane from the audience. The actor may choose to speak any dialect of Mandarin, but the ancient Zhōngzhōu (Chinese: 中州; Jyutping: Zung1 Zau1) variant is mainly used in Cantonese opera. Zhōngzhōu is located in the modern-day Henan province where it is considered the "cradle of Chinese civilization" and near the Yellow River. Guān Huà retains many of the initial sounds of many modern Mandarin dialects, but uses initials and codas from Middle Chinese. For example, the words 張 and 將 are both pronounced as /tsœːŋ˥˥/ (Jyutping: zœng1) in Modern Cantonese, but will respectively be spoken as /tʂɑŋ˥˥/ (pinyin: zhāng) and /tɕiɑŋ˥˥/ (pinyin: jiāng) in operatic Guān Huà. Furthermore, the word 金 is pronounced as /kɐm˥˥/ (Jyutping: gam1) in modern Cantonese and /tɕin˥˥/ (pinyin: jīn) in standard Mandarin, but operatic Guān Huà will use /kim˥˥/ (pinyin: gīm). However, actors tend to use Cantonese sounds when speaking Mandarin. For instance, the command for "to leave" is 下去 and is articulated as /saː˨˨ tsʰɵy˧˧/ in operatic Guān Huà compared to /haː˨˨ hɵy˧˧ / (Jyutping: haa6 heoi3) in modern Cantonese and /ɕi̯ɑ˥˩ tɕʰy˩/ (pinyin: xià qu) in standard Mandarin.

Music

[edit]Cantonese opera pieces are classified either as "theatrical" or "singing stage" (歌壇). The theatrical style of music is further classified into western music (西樂) and Chinese music (中樂). While the "singing stage" style is always Western music, the theatrical style can be Chinese or western music. The "four great male vocals" (四大平喉) were all actresses and notable exponents of the "singing stage" style in the early 20th century.

The western music in Cantonese opera is accompanied by strings, woodwinds, brass plus electrified instruments. Lyrics are written to fit the play's melodies, although one song can contain multiple melodies, performers being able to add their own elements. Whether a song is well performed depends on the performers' own emotional involvement and ability.

Musical instruments

[edit]

Cantonese instrumental music was called ching yam before the People's Republic was established in 1949. Cantonese instrumental tunes have been used in Cantonese opera, either as incidental instrumental music or as fixed tunes to which new texts were composed, since the 1930s.

The use of instruments in Cantonese opera is influenced by both western and eastern cultures. The reason for this is that Canton was one of the earliest places in China to establish trade relationships with the western civilizations. In addition, Hong Kong was under heavy western influence when it was a British colony. These factors contributed to the observed western elements in Cantonese opera.

For instance, the use of erhu (two string bowed fiddle), saxophones, guitars and the congas have demonstrated how diversified the musical instruments in Cantonese operas are.

The musical instruments are mainly divided into melodic and percussive types.

Traditional musical instruments used in Cantonese opera include wind, strings and percussion. The winds and strings encompass erhu, gaohu, yehu, yangqin, pipa, dizi, and houguan, while the percussion comprises many different drums and cymbals. The percussion controls the overall rhythm and pace of the music, while the gaohu leads the orchestra. A more martial style features the use of the suona.

The instrumental ensemble of Cantonese opera is composed of two sections: the melody section and the percussion section. The percussion section has its own vast body of musical materials, generally called lo gu dim (鑼鼓點) or simply lo gu (鑼鼓). These 'percussion patterns' serve a variety of specific functions.

To see the pictures and listen to the sounds of the instruments, visit page 1 and page 2.

Terms

[edit]This is a list of frequently used terms.

- Pheasant feathers (雉雞尾; Cantonese: Ci4 Gai1 Mei5)

- These are attached to the helmet in mou (武) plays, and are used to express the character's skills and expressions. They are worn by both male and female characters.

- Water sleeves (水袖; Cantonese: Seoi2 Zau6)

- These are long flowing sleeves that can be flicked and waved like water, used to facilitate emotive gestures and expressive effects by both males and females in man (文) plays.

- Hand Movements (手動作; Cantonese: Sau2 Dung6 Zok3)

- Hand and finger movements reflect the music as well as the action of the play. Females hold their hands in the elegant "lotus" form (荷花手; Cantonese: Ho4 Faa1 Sau2).

- Round Table/Walking (圓臺 or 圓台; Cantonese: Jyun4 Toi4)

- A basic feature of Cantonese opera, the walking movement is one of the most difficult to master. Females take very small steps and lift the body to give a detached feel. Male actors take larger steps, which implies travelling great distances. The actors glide across the stage while the upper body is not moving.

- Boots (高靴; Cantonese: Gou1 Hœ1)

- Gwo Wai (過位; Cantonese: Gwo3 Wai6/2)

- This is a movement in which two performers move in a cross-over fashion to opposite sides of the stage.

- Deoi Muk (對目; Cantonese: Deoi3 Muk6)

- In this movement, two performers walk in a circle facing each other and then go back to their original positions.

- "Pulling the Mountains"' (拉山; Cantonese: Laai1 Saan1) and "Cloud Hands" (雲手; Cantonese: Wan4 Sau2)

- These are the basic movements of the hands and arms. This is the MOST important basic movement in ALL Chinese Operas. ALL other movements and skills are based on this form.

- Outward Step (出步; Cantonese: Ceot1 Bou6)

- This is a gliding effect used in walking.

- Small Jump (小跳; Cantonese: Siu2 Tiu3)

- Most common in mou (武) plays, the actor stamps before walking.

- Flying Leg (飛腿; Cantonese: Fei1 Teoi2)

- A crescent kick.

- Hair-flinging (旋水髮; Cantonese: Syun4 Seoi2 Faat3)

- A circular swinging of the ponytail, expressing extreme sadness and frustration.

- Chestbuckle/ Flower (繡花; Cantonese: Sau3 Faa1)

- A flower-shaped decoration worn on the chest. A red flower on the male signifies that he is engaged.

- Horsewhip (馬鞭; Cantonese: Maa5 Bin1)

- Performers swing a whip and walk to imitate riding a horse.

- Sifu (師傅; Cantonese: Si1 Fu6/2)

- Literally, master, this is a formal term, contrary to mentor, for experienced performers and teachers, from whom their own apprentices, other students and young performers learn and follow as disciples.

See also

[edit]- Cantopop

- Red Boat Opera Company

- Music of China

- Music of Hong Kong

- Culture of Hong Kong

- Hong Kong Heritage Museum

- Chinese Artists Association of Hong Kong

References

[edit]- ^ 宋, 钻友 (1994). "粤剧在旧上海的演出" (1): 64–70.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[permanent dead link] - ^ Zhong, Zhe Ping (2014). "旧上海,粤剧夜夜笙歌之地". 南国红豆. 06: 51–53 – via HSU Database.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Danwu Hou (28 October 2017), 上海故事 – 324 粤剧粤乐(上), archived from the original on 12 December 2021, retrieved 28 February 2019

- ^ Cheng, Mei Po (2007). "The Trans-locality of Local Cultures in Modem China: Cantonese Opera, Music, and Songs in Shanghai, 1920s–1930s". China Agricultural University. 2007: 1–17 – via HSU Library Database.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Wordie, Jason (2002). Streets: Exploring Hong Kong Island. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-563-1.

- ^ 許, 國惠 (2016). "1950–1960年代香港左派對新中國戲曲電影的推廣". 南京大學學報(哲學·人文科學·社會科學). 53 (2): 137–149.

- ^ "戲台上下—香港戲院與粵劇" (PDF). Hong Kong Heritage Museum Leisure And Cultural Services Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ "立法會十九題:粵劇的承傳及發展". 政府新聞網. 21 October 2009. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ "Life-long performance record of Lam Kar Sing". Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Farewell of Zhu Bian Returns to Court《朱弁回朝》之「送別」

- ^ Song 6 of Lam Ka Sing Best Selection 3.《情醉王大儒》之「供狀」

- ^ Lam talked about spy or espionage among those around him, on radio in mid1980s.「紅伶訴心聲」

- ^ Lam Ka Sing Classics Collection (DVD) (Hong Kong Version), episode 14.

- ^ Lam Ka Sing Classics Collection (DVD) (Hong Kong Version), episode 11 and 12.

- ^ Lam was eager to hand his traditions down to a young performer who was pushing Lam's wheelchair in the 2015 event.

- ^ "Appointments to Cantonese Opera Development Fund Advisory Committee". Archived from the original on 4 November 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ "Acknowledgement Guidelines (General)". Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ Background and Objectives Last Updated on Tuesday, 17 July 2018

- ^ "The ADC expresses deep sorrow over the passing of renowned Cantonese opera veteran Chan Kim-seng". Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ LO, W. (2015). The music culture of older adults in Cantonese operatic singing lessons. Ageing and Society, 35(8), 1614–1634. doi:10.1017/S0144686X14000439

- ^ Wai Han Lo (2016) Traditional opera and young people: Cantonese opera as personal development, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22:2, 238–249, DOI: 10.1080/02673843.2016.1163503

- ^ "More on Cantonese Opera". Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Li, Wan Xia (2014). "清代粵港澳神功戲演出及其場所". 戲曲品味. 159: 77–79 – via HSU Library Database.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Opera of Deities". Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "戲曲視窗:神功戲與香港粵劇存亡". Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ 王勝泉, 張文珊(2011)編,香港當代粵劇人名錄,中大音樂系 The Chinese University Press (Description and Author Information) Archived 25 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-988-19881-1-9

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ His wife Yu So-chow

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ HKFA document YAM Bing-yee Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine Yam has been acclaimed as "The Queen of Second Lead Actresses".

- ^ "Rehearsal of "Merciless Sword Under Merciful Heaven" (19.1.2016)". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Lam Kar Sing". Virtuosity and Innovation – The Masterful Legacy of Lam Kar Sing 20 July 2011 – 14 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ Credited as Leng Chi Pak, 'King of Chinese opera' to step down at 72, New Nation, 20 October 1976, Page 4

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ "Artistic Director:Yuen Siu-fai". Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Awardee List 2010". Hong Kong Arts Development Council. 2010. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ "Artistic Director:Wan Fai-yin". Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ https://www.facebook.com/mayying.ng.14?fref=ts [user-generated source]

- ^ https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100003314793077 [user-generated source]

- ^ "Rehearsal of "Red Silk Shoes and The Murder" (16.1.2016)". Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Artistic Director:Law Ka-ying". Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Stokes, Lisa Odham (2007). Historical Dictionary of Hong Kong Cinema. Scarecrow Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 9780810864580. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Iconic Heroines in Cantonese Opera Films

- ^ a b "Ng Kwun-Lai". A Synthesis of Lyrical Excellence and Martial Agility – The Stage Art of Ng Kwan Lai 22 December 2004 – 15 September 2005. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Chan Yim Nung". hkmdb.com. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ "Cantonese Opera Shoes (used by female actors to represent women with bound feet)". rrncommunity.org. Item number N1.764 a-b from the MOA: University of British Columbia. They were used only until about 1935, after which the knowledge of how to use them was lost. An actress named Chan Yim-nung was especially famous for her use of these shoes, and could jump on and off tables and stand on clay pots while wearing them. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Nangaen Chearavanont; Au Ho; Ou Chiu Shui (2013). "Ch 8 - Wah Ngai Film Company". Film Stories: (Bangkok, Hong Kong, Singapore, Canton, San Francisco.). Silent film See the Bud in Fading directed by Mr. Chiang Pai-ku of Wah Ngai Film Company. Hong Kong: H.M. Ou. p. 50. ISBN 9789881590947.

- ^ Story of Mei in the North and Suet in the South 戲曲視窗:「北梅南雪」的故事 – 香港文匯報 2016-01-26

- ^ "Ms Fong Yim Fun, 1928-, Actress". avenueofstars.com.hk. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Heritage Museum Exhibition to feature the female Cantonese opera artist Fong Yim Fun as of 8 October 2002". Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ McHugh, Fionnuala (16 July 1998). "The queen who came back to her people". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 15 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ Credited as Li Po-ying, Operatic revival, The Straits Times, 3 July 1982, Page 4.

- ^ CANTONESE OPERA YOUNG TALENT SHOWCASE – Artists Archived 16 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine Only about 15 in male costumes are lead actors. Actresses dominate as a result of the Yam-Loong Effect for over five decades. Both Koi Ming Fai and Lau Wai Ming were not old enough to be in the audience for Yam's final performance on stage in 1969.

- ^ "Cantonese Opera Day 2016 - Cecilia Lee Fung-sing's Legendary Rise to Opera - Introduction". lcsd.gov.hk. 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Press Releases - Film Archive to screen Cantonese opera films of Cecilia Lee Fung-sing in support of Cantonese Opera Day 2016 (with photos)". info.gov.hk. 25 October 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Cecelia Lee Fung-Sing". hkmdb.com. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d Famed female Cantonese opera singers Xiao Minxin, Xu Liu-xian, Zhang Yue'r and Zhang Hui-fang 6 December 2011 Hong Kong Central Library

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ Kwai Ming Yeung style 聽"桂派"名曲 藝海 2010-07-08

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ HKMDB

- ^ Chan, Sau Y. (March 2005). "Performance Context as a Molding Force: Photographic Documentation of Cantonese Opera in Hong Kong". Visual Anthropology. 18 (2–3): 167–198. doi:10.1080/08949460590914840. ISSN 0894-9468. S2CID 145687247.

- ^ 2010 to 2015 Time table Archived 16 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine of Chinese Artist Association of Hong Kong 香港八和會館 神功戲台期表

- ^ "香港戲棚文化". HOKK fabrica. 29 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ 知多一點點2 (3 May 2015), 粵劇智識知多的, archived from the original on 12 December 2021, retrieved 8 March 2019

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Maybe The Cantonese Opera Diva Archived 24 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine 1 January 2016 Australia

- ^ 舞台下的龍劍笙 Archived 29 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine 14 November 2015 Hong Kong