Iowa-class battleship

USS Iowa (BB-61) fires a full broadside on 15 August 1984 during a firepower demonstration after her recommissioning

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Iowa-class battleship |

| Builders |

|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | South Dakota class |

| Succeeded by | Montana class (planned) |

| Cost | US$100 million per ship |

| Built | 1940–1944 |

| In commission |

|

| Planned | 6 |

| Completed | 4 |

| Cancelled | 2 |

| Retired | 4 |

| Preserved | 4 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 108 ft 2 in (32.97 m) |

| Draft |

|

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × screws; 4 × geared steam turbines |

| Speed | 33 knots (61.1 km/h; 38.0 mph) (up to 35.2 knots (65.2 km/h; 40.5 mph) at light load) |

| Range | 14,890 nmi (27,580 km; 17,140 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Electronic warfare & decoys |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

| Aircraft carried |

|

| Aviation facilities |

|

The Iowa class was a class of six fast battleships ordered by the United States Navy in 1939 and 1940. They were initially intended to intercept fast capital ships such as the Japanese Kongō class and serve as the "fast wing" of the U.S. battle line.[3][4] The Iowa class was designed to meet the Second London Naval Treaty's "escalator clause" limit of 45,000-long-ton (45,700 t) standard displacement. Beginning in August 1942, four vessels, Iowa, New Jersey, Missouri, and Wisconsin, were completed; two more, Illinois and Kentucky, were laid down but canceled in 1945 and 1958, respectively, before completion, and both hulls were scrapped in 1958–1959.

The four Iowa-class ships were the last battleships commissioned in the U.S. Navy. All older U.S. battleships were decommissioned by 1947 and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register (NVR) by 1963. Between the mid-1940s and the early 1990s, the Iowa-class battleships fought in four major U.S. wars. In the Pacific Theater of World War II, they served primarily as fast escorts for Essex-class aircraft carriers of the Fast Carrier Task Force and also shelled Japanese positions. During the Korean War, the battleships provided naval gunfire support (NGFS) for United Nations forces, and in 1968, New Jersey shelled Viet Cong and Vietnam People's Army forces in the Vietnam War. All four were reactivated and modernized at the direction of the United States Congress in 1981, and armed with missiles during the 1980s, as part of the 600-ship Navy initiative. During Operation Desert Storm in 1991, Missouri and Wisconsin fired missiles and 16-inch (406 mm) guns at Iraqi targets.

Costly to maintain, the battleships were decommissioned during the post-Cold War drawdown in the early 1990s. All four were initially removed from the Naval Vessel Register, but the United States Congress compelled the Navy to reinstate two of them on the grounds that existing shore bombardment capability would be inadequate for amphibious operations. This resulted in a lengthy debate over whether battleships should have a role in the modern navy. Ultimately, all four ships were stricken from the Naval Vessel Register and released for donation to non-profit organizations. With the transfer of Iowa in 2012, all four are museum ships part of non-profit maritime museums across the US.

Background

[edit]The vessels that eventually became the Iowa-class battleships were born from the U.S. Navy's War Plan Orange, a Pacific war plan against Japan. War planners anticipated that the U.S. fleet would engage and advance in the Central Pacific, with a long line of communication and logistics that would be vulnerable to high-speed Japanese cruisers and capital ships. The chief concern was that the U.S. Navy's traditional 21-knot battle line of "Standard-type" battleships would be too slow to force these Japanese task forces into battle, while faster aircraft carriers and their cruiser escorts would be outmatched by the Japanese Kongō-class battlecruisers, which had been upgraded in the 1930s to fast battleships. As a result, the U.S. Navy envisioned a fast detachment of the battle line that could bring the Japanese fleet into battle. Even the new standard battle line speed of 27 knots, as the preceding North Carolina-class and South Dakota-class battleships were designed for, was not considered enough and during their development processes, designs that could achieve over 30 knots in order to counter the threat of fast "big gun" ships were seriously considered.[5][6] At the same time, a special strike force consisting of fast battleships operating alongside carriers and destroyers was being envisaged; such a force could operate independently in advance areas and act as scouts. This concept eventually evolved into the Fast Carrier Task Force, though initially the carriers were believed to be subordinate to the battleship.[4]

Another factor was the "escalator clause" of the Second London Naval Treaty, which reverted the gun caliber limit from 14 inches (356 mm) to 16 inches (406 mm). Japan had refused to sign the treaty and in particular refused to accept the 14-inch gun caliber limit or the 5:5:3 ratio of warship tonnage limits for Britain, the United States, and Japan, respectively. This resulted in the three treaty powers, the United States, Britain, and France, invoking the caliber escalator clause after April 1937. Circulation of intelligence evidence in November 1937 of Japanese capital ships violating naval treaties caused the treaty powers to expand the escalator clause in June 1938, which amended the standard displacement[N 1] limit of battleships from 35,000 long tons (35,600 t) to 45,000 long tons (45,700 t).[8]

Design

[edit]Early studies

[edit]Work on what would eventually become the Iowa-class battleship began on the first studies in early 1938, at the direction of Admiral Thomas C. Hart, head of the General Board, following the planned invocation of the "escalator clause" that would permit maximum standard capital ship displacement of 45,000 long tons (45,700 t). Using the additional 10,000 long tons (10,200 t) over previous designs, the studies included schemes for 27-knot (50 km/h; 31 mph) "slow" battleships that increased armament and protection as well as "fast" battleships capable of 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) or more. One of the "slow" designs was an expanded South Dakota class carrying either twelve 16-inch/45 caliber Mark 6 guns or nine 18-inch (457 mm)/48 guns and with more armor and a power plant large enough to drive the larger ship through the water at the same 27-knot maximum speed as the South Dakotas.[N 2] While the "fast" studies would result in the Iowa class, the "slow" design studies would eventually settle on twelve 16-inch guns and evolve into the design for the 60,500-long-ton (61,500 t) Montana class after all treaty restrictions were removed following the start of World War II.[10] Priority was given to the "fast" design in order to counter and defeat Japan's 30-knot (56 km/h; 35 mph)[11] Kongō-class fast battleships, whose higher speed advantage over existing U.S. battleships might let them "penetrate U.S. cruisers, thereby making it 'open season' on U.S. supply ships",[12] and then overwhelm the Japanese battle line was therefore a major driving force in setting the design criteria for the new ships, as was the restricting width of the Panama Canal.[11]

For "fast" battleships, one such design, pursued by the Design Division section of the Bureau of Construction and Repair, was a "cruiser-killer". Beginning on 17 January 1938, under Captain A.J. Chantry, the group drew up plans for ships with twelve 16-inch and twenty 5-inch (127 mm) guns, Panamax capability but otherwise unlimited displacement, a top speed of 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph) and a range of 20,000 nautical miles (37,000 km; 23,000 mi) when traveling at the more economical speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph). Their plan fulfilled these requirements with a ship of 50,940 long tons (51,760 t) standard displacement, but Chantry believed that more could be done if the ship were to be this large; with a displacement greater than that of most battleships, its armor would have protected it only against the 8-inch (200 mm) weapons carried by heavy cruisers.[13]

Three improved plans – "A", "B", and "C" – were designed at the end of January. An increase in draft, vast additions to the armor,[N 3] and the substitution of twelve 6-inch (152 mm) guns in the secondary battery were common among the three designs. "A" was the largest, at 59,060 long tons (60,010 t) standard, and was the only one to still carry the twelve 16-inch guns in four triple turrets (3-gun turrets according to US Navy). It required 277,000 shp (207,000 kW) to make 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph). "B" was the smallest at 52,707 long tons (53,553 t) standard; like "A" it had a top speed of 32.5 knots, but "B" only required 225,000 shp (168,000 kW) to make this speed. It also carried only nine 16-inch guns, in three triple turrets. "C" was similar but added 75,000 shp (56,000 kW) (for a total of 300,000 shp (220,000 kW)) to meet the original requirement of 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph). The weight required for this and a longer belt – 512 feet (156 m), compared with 496 feet (151 m) for "B" – meant that the ship was 55,771 long tons (56,666 t) standard.[14]

Design history

[edit]In March 1938, the General Board followed the recommendations of the Battleship Design Advisory Board, which was composed of the naval architect William Francis Gibbs, William Hovgaard (then president of New York Shipbuilding), John Metten, Joseph W. Powell, and the long-retired Admiral and former Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance Joseph Strauss. The board requested an entirely new design study, again focusing on increasing the size of the 35,000-long-ton (36,000 t) South Dakota class. The first plans made for this indicated that 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) was possible on a standard displacement of about 37,600 long tons (38,200 t). 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) could be bought with 220,000 shp (160,000 kW) and a standard displacement of around 39,230 long tons (39,860 t), which was well below the London Treaty's "escalator clause" maximum limit of 45,000 long tons (45,700 t).[15]

These designs were able to convince the General Board that a reasonably well-designed and balanced 33-knot "fast" battleship was possible within the terms of the "escalator clause". However, further studies revealed major problems with the estimates. The speed of the ships meant that more freeboard would be needed both fore and amidships, the latter requiring an additional foot of armored freeboard. Along with this came the associated weight in supporting these new strains: the structure of the ship had to be reinforced and the power plant enlarged to avoid a drop in speed. In all, about 2,400 long tons (2,440 t) had to be added, and the large margin the navy designers had previously thought they had – roughly 5,000 long tons (5,080 t) – was suddenly vanishing.[16] The draft of the ships was also allowed to increase, which enabled the beam to narrow and thus reduced the required power (since a lower beam-to-draft ratio reduces wave-making resistance). This also allowed the ships to be shortened, which reduced weight.[17]

With the additional displacement, the General Board was incredulous that a tonnage increase of 10,000 long tons (10,200 t) would allow only the addition of 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph) over the South Dakotas. Rather than retaining the 16-inch/45 caliber Mark 6 guns used in the South Dakotas, they ordered that the preliminary design would have to include the more powerful but significantly heavier 16-inch/50 caliber Mark 2 guns left over from the canceled Lexington-class battlecruisers and South Dakota-class battleships of the early 1920s.[17]

The 16"/50 turret weighed some 400 long tons (406 t) more than the 16"/45 turret already in use and also had a larger barbette diameter of 39 feet 4 inches (11.99 m) compared to the latter's barbette diameter of 37 feet 3 inches (11.35 m), so the total weight gain was about 2,000 long tons (2,030 t). This put the ship at a total of 46,551 long tons (47,298 t) – well over the 45,000-long-ton (46,000 t) limit. An apparent savior appeared in a Bureau of Ordnance preliminary design for a turret that could carry the 50-caliber guns and also fit in the smaller barbette of the 45-caliber gun turret. Other weight savings were achieved by thinning some armor elements and substituting construction steel with armor-grade Special Treatment Steel (STS) in certain areas. The net savings reduced the preliminary design displacement to 44,560 long tons (45,280 t) standard, though the margin remained tight. This breakthrough was shown to the General Board as part of a series of designs on 2 June 1938.[18]

However, the Bureau of Ordnance continued working on the turret with the larger barbette, while the Bureau of Construction and Repair used the smaller barbettes in the contract design of the new battleships. As the bureaus were independent of one another, they did not realize that the two plans could not go together until November 1938, when the contract design was in the final stages of refinement. By this time, the ships could not use the larger barbette, as it would require extensive alterations to the design and would result in substantial weight penalties. Reverting to the 45-caliber gun was also deemed unacceptable. The General Board was astounded; one member asked the head of the Bureau of Ordnance if it had occurred to him that Construction and Repair would have wanted to know what turret his subordinates were working on "as a matter of common sense". A complete scrapping of plans was avoided only when designers within the Bureau of Ordnance were able to design a new 50-caliber gun, the Mark 7, that was both lighter and smaller in outside diameter; this allowed it to be placed in a turret that would fit in the smaller barbette. The redesigned 3-gun turret, equipped as it was with the Mark 7 naval gun, provided an overall weight saving of nearly 850 long tons (864 t) to the overall design of the Iowa class. The contract design displacement subsequently stood at 45,155 long tons (45,880 t) standard and 56,088 long tons (56,988 t) full load.[19]

In May 1938, the United States Congress passed the Second Vinson Act, which "mandated a 20% increase in strength of the United States Navy".[20] The act was sponsored by Carl Vinson, a Democratic Congressman from Georgia who was Chairman of the House Naval Affairs and Armed Services Committee.[21] The Second Vinson Act updated the provisions of the Vinson-Trammell Act of 1934 and the Naval Act of 1936, which had "authorized the construction of the first American battleships in 17 years", based on the provisions of the London Naval Treaty of 1930;[20] this act was quickly signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and provided the funding to build the Iowa class. Each ship cost approximately US$100 million.[22]

As 1938 drew to a close, the contract design of the Iowas was nearly complete, but it would continuously evolve as the New York Navy Yard, the lead shipyard, conducted the final detail design. These revisions included changing the design of the foremast, replacing the original 1.1-inch (27.9 mm)/75-caliber guns that were to be used for anti-aircraft (AA) work with 20 mm (0.79 in)/70 caliber Oerlikon cannons and 40 mm (1.57 in)/56 caliber Bofors guns, and moving the combat information center into the armored hull.[23] Additionally, in November 1939, the New York Navy Yard greatly modified the internal subdivision of the machinery rooms, as tests had shown the underwater protection in these rooms to be inadequate. The longitudinal subdivision of these rooms was doubled, and the result of this was clearly beneficial: "The prospective effect of flooding was roughly halved and the number of uptakes and hence of openings in the third deck greatly reduced." Although the changes meant extra weight and increasing the beam by 1 foot (0.30 m) to 108 feet 2 inches (32.97 m), this was no longer a major issue; Britain and France had renounced the Second London Naval Treaty soon after the beginning of the Second World War.[24] The design displacement was 45,873 long tons (46,609 t) standard, approximately 2% overweight, when Iowa and New Jersey were laid down in June and September 1940. By the time the Iowas were completed and commissioned in 1943–44, the considerable increase in anti-aircraft armament – along with their associated splinter protection and crew accommodations – and additional electronics had increased standard displacement to some 47,825 long tons (48,592 t), while full load displacement became 57,540 long tons (58,460 t).[25][26][27]

For half a century prior to laying [the Iowa class] down, the US Navy had consistently advocated armor and firepower at the expense of speed. Even in adopting fast battleships of the North Carolina class, it had preferred the slower of two alternative designs. Great and expensive improvements in machinery design had been used to minimize the increased power on the designs rather than make extraordinary powerful machinery (hence much higher speed) practical. Yet the four largest battleships the US Navy produced were not much more than 33-knot versions of the 27-knot, 35,000 tonners that had preceded them. The Iowas showed no advance at all in protection over the South Dakotas. The principal armament improvement was a more powerful 16-inch gun, 5 calibers longer. Ten thousand tons was a very great deal to pay for 6 knots.

Specifications

[edit]General characteristics

[edit]

The Iowa-class battleships are 860 ft 0 in (262.13 m) long at the waterline and 887 ft 3 in (270.43 m) long overall with a beam of 108 ft 2 in (32.97 m).[N 4] During World War II, the draft was 37 ft 2 in (11.33 m) at full load displacement of 57,540 long tons (58,460 t) and 34 ft 9+1⁄4 in (10.60 m) at design combat displacement of 54,889 long tons (55,770 t). Like the two previous classes of American fast battleships, the Iowas have a double bottom hull that becomes a triple bottom under the armored citadel and armored skegs around the inboard shafts.[30] The dimensions of the Iowas were strongly influenced by speed. When the Second Vinson Act was passed by the United States Congress in 1938, the U.S. Navy moved quickly to develop a 45,000-ton-standard battleship that would pass through the 110 ft (34 m) wide Panama Canal. Drawing on a 1935 empirical formula for predicting a ship's maximum speed based on scale-model studies in flumes of various hull forms and propellers[N 5] and a newly developed empirical theorem that related waterline length to maximum beam, the Navy drafted plans for a battleship class with a maximum beam of 108 ft 2 in (32.97 m) which, when multiplied by 7.96, produced a waterline length of 860 ft (262 m).[20] The Navy also called for the class to have a lengthened forecastle and amidship, which would increase speed, and a bulbous bow.[32]

The Iowas exhibit good stability, making them steady gun platforms. At design combat displacement, the ships' (GM) metacentric height was 9.26 ft (2.82 m).[30] They also have excellent maneuverability in the open water for their size, while seakeeping is described as good, but not outstanding. In particular, the long fine bow and sudden widening of the hull just in front of the foremost turret contributed to the ships being rather wet for their size. This hull form also resulted in very intense spray formations, which led to some difficulty refueling escorting destroyers.[33][34]

Armament

[edit]Main battery

[edit]The primary guns used on these battleships are the nine 16-inch (406 mm)/50-caliber Mark 7 naval guns, a compromise design developed to fit inside the barbettes. These guns fire high explosive- and armor-piercing shells and can fire a 16-inch shell approximately 23.4 nautical miles (43.3 km; 26.9 mi).[35][36] The guns are housed in three 3-gun turrets: two forward of the battleship's superstructure and one aft, in a configuration known as "2-A-1". The guns are 66 feet (20 m) long (50 times their 16-inch bore, or 50 calibers from breechface to muzzle). About 43 feet (13 m) protrudes from the gun house. Each gun weighs about 239,000 pounds (108,000 kg) without the breech, or 267,900 pounds (121,500 kg) with the breech.[36] They fired 2,700-pound (1,225 kg) armor-piercing projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,500 ft/s (762 m/s), or 1,900-pound (862 kg) high-capacity projectiles at 2,690 ft/s (820 m/s), up to 24 miles (21 nmi; 39 km).[N 6] At maximum range, the projectile spends almost 1+1⁄2 minutes in flight. The maximum firing rate for each gun is two rounds per minute.[38]

Each gun rests within an armored turret, but only the top of the turret protrudes above the main deck. The turret extends either four decks (Turrets 1 and 3) or five decks (Turret 2) down. The lower spaces contain rooms for handling the projectiles and storing the powder bags used to fire them. Each turret required a crew of between 85 and 110 men to operate.[36] The original cost for each turret was US$1.4 million, but this figure does not take into account the cost of the guns themselves.[36] The turrets are "three-gun", not "triple", because each barrel is individually sleeved and can be elevated and fired independently. The ship could fire any combination of its guns, including a broadside of all nine. The fire control was performed by the Mark 38 Gun Fire Control System (GFCS); the firing solutions were computed with the Mark 8 rangekeeper, an analog computer that automatically receives information from the director and Mark 8/13 fire control radar, stable vertical, ship pitometer log and gyrocompass, and anemometer. The GFCS uses remote power control (RPC) for automatic gun laying.[39]

The large-caliber guns were designed to fire two different conventional 16-inch shells: the 2,700-pound (1,225 kg) Mk 8 "Super-heavy" APC (Armor Piercing, Capped) shell for anti-ship and anti-structure work, and the 1,900-pound (862 kg) Mk 13 high-explosive round designed for use against unarmored targets and shore bombardment.[40] When firing the same conventional shell, the 16-inch/45 caliber Mark 6 used by the fast battleships of the North Carolina and South Dakota classes had a slight advantage over the 16-inch/50 caliber Mark 7 gun when hitting deck armor – a shell from a 45 cal gun would be slower, meaning that it would have a steeper trajectory as it descended. At 35,000 yards (20 mi; 32 km), a shell from a 45 cal would strike a ship at an angle of 45.2 degrees, as opposed to 36 degrees with the 50 cal.[41] The Mark 7 had a greater maximum range over the Mark 6: 23.64 miles (38.04 km) vs 22.829 miles (36.740 km).[N 6][41][42]

In the 1950s, the W23, an adaptation of the W19 nuclear artillery shell, was developed specifically for the 16-inch guns. The shell weighed 1,900 pounds (862 kg), had an estimated yield of 15 to 20 kilotons of TNT (63,000 to 84,000 GJ),[43] and its introduction made the Iowa-class battleships' 16-inch guns the world's largest nuclear artillery[44] and made these four battleships the only US Navy ships ever to have nuclear shells for naval guns.[44] Although developed for exclusive use by the battleship's guns it is not known if any of the Iowas actually carried these shells while in active service due to the United States Navy's policy of refusing to confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weaponry aboard its ships.[45][N 7] In 1991, the United States unilaterally withdrew all of its nuclear artillery shells from service, and the dismantling of the US nuclear artillery inventory is said to have been completed in 2004.[47]

Secondary battery

[edit]

The Iowas carried twenty 5-inch (127 mm)/38 caliber Mark 12 guns in ten Mark 28 Mod 2 enclosed base ring mounts. Originally designed to be mounted upon destroyers built in the 1930s, these guns were so successful that they were added to many American ships during the Second World War, including every major ship type and many smaller warships constructed between 1934 and 1945. They were considered to be "highly reliable, robust and accurate" by the Navy's Bureau of Ordnance.[48]

Each 5-inch/38 gun weighed almost 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) without the breech; the entire mount weighed 156,295 pounds (70,894 kg). It was 223.8 inches (5,680 mm) long overall, had a bore length of 190 inches (4,800 mm), and a rifling length of 157.2 inches (3,990 mm). The gun could fire shells at about 2,500–2,600 ft/s (760–790 m/s); about 4,600 could be fired before the barrel needed to be replaced. Minimum and maximum elevations were −15 and 85 degrees, respectively. The guns' elevation could be raised or lowered at about 15 degrees per second. The mounts closest to the bow and stern could aim from −150 to 150 degrees; the others were restricted to −80 to 80 degrees. They could be turned at about 25 degrees per second. The mounts were directed by four Mark 37 fire control systems primarily through remote power control (RPC).[48]

The 5-inch/38 gun functioned as a dual-purpose gun (DP); that is, it was able to fire at both surface and air targets with a reasonable degree of success. However, this did not mean that it possessed inferior anti-air abilities. As proven during 1941 gunnery tests conducted aboard North Carolina the gun could consistently shoot down aircraft flying at 12,000–13,000 feet (2.3–2.5 mi; 3.7–4.0 km), twice the effective range of the earlier single-purpose 5-inch/25 caliber AA gun.[48] As Japanese airplanes became faster, the gun lost some of its effectiveness in the anti-aircraft role; however, toward the end of the war, its usefulness as an anti-aircraft weapon increased again because of an upgrade to the Mark 37 Fire Control System, Mark 1A computer, and proximity-fused shells.[49][50]

The 5-inch/38 gun would remain on the battleships for the ships' entire service life; however, the total number of guns and gun mounts was reduced from twenty guns in ten mounts to twelve guns in six mounts during the 1980s' modernization of the four Iowas. The removal of four of the gun mounts was required for the battleships to be outfitted with the armored box launchers needed to carry and fire Tomahawk missiles. At the time of the 1991 Persian Gulf War, these guns had been largely relegated to littoral defense for the battleships. Since each battleship carried a small detachment of Marines aboard, the Marines would man one of the 5-inch gun mounts.[51]

Anti-air battery

[edit]

At the time of their commissioning, all four of the Iowa-class battleships were equipped with 20 quad 40 mm mounts and 49 single 20 mm mounts.[52] These guns were respectively augmented with the Mk 14 range sight and Mk 51 fire control system to improve accuracy.

The Oerlikon 20-millimeter (0.8 in) gun, one of the most heavily produced anti-aircraft guns of the Second World War, entered service in 1941 and replaced the 0.50-inch (12.7 mm) M2 Browning MG on a one-for-one basis. Between December 1941 and September 1944, 32% of all Japanese aircraft downed were credited to this weapon, with the high point being 48.3% for the second half of 1942; however, the 20 mm guns were found to be ineffective against the Japanese Kamikaze attacks used during the latter half of World War II and were subsequently phased out in favor of the heavier Bofors 40-millimeter (1.6 in) AA gun.[53]

When the Iowa-class battleships were commissioned in 1943 and 1944, they carried twenty quad 40 mm AA gun mounts, which they used for defense against enemy aircraft. These heavy AA guns were also employed in the protection of Allied aircraft carriers operating in the Pacific Theater of World War II, and accounted for roughly half of all Japanese aircraft shot down between 1 October 1944 and 1 February 1945.[54][55][N 8] Although successful in this role against WWII aircraft, the 40 mm guns were stripped from the battleships in the jet age – initially from New Jersey when reactivated in 1968[56] and later from Iowa, Missouri, and Wisconsin when they were reactivated for service in the 1980s.[N 9]

Propulsion

[edit]The powerplant of the Iowas consists of eight Babcock & Wilcox boilers and four sets of double reduction cross-compound geared turbines, with each turbine set driving a single shaft. Specifically, the geared turbines on Iowa and Missouri were provided by General Electric, while the equivalent machinery on New Jersey and Wisconsin was provided by Westinghouse.[58][59] The plant produced 212,000 shp (158,000 kW) and propelled the ship up to a maximum speed of 32.5 kn (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) at full load displacement and 33 kn (61 km/h; 38 mph) at normal displacement.[N 10] The ships carried 8,841 long tons (8,983 t) of fuel oil which gave a range of 15,900 nmi (29,400 km; 18,300 mi) at 17 kn (31 km/h; 20 mph). Two semi-balanced rudders gave the ships a tactical turning diameter of 814 yards (744 m) at 30 kn (56 km/h; 35 mph) and 760 yards (695 m) at 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph).[25]

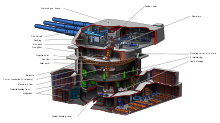

The machinery spaces were longitudinally divided into eight compartments with alternating fire and engine rooms to ensure adequate isolation of machinery components. Four fire rooms each contained two M-Type boilers operating at 600 pounds per square inch (4,137 kPa; 42 kgf/cm2) with a maximum superheater outlet temperature of 850 °F (454 °C).[59][64] The double-expansion engines consist of a high-pressure (HP) turbine and a low-pressure (LP) turbine. The steam is first passed through the HP turbine which turns at up to 2,100 rpm. The steam, largely depleted at this point, is then passed through a large conduit to the LP turbine. By the time it reaches the LP turbine, it has no more than 50 psi (340 kPa) of pressure left. The LP turbine increases efficiency and power by extracting the last little bit of energy from the steam. After leaving the LP turbine, the exhaust steam passes into a condenser and is then returned as feed water to the boilers. Water lost in the process is replaced by three evaporators, which can make a total of 60,000 US gallons per day (3 liters per second) of fresh water. After the boilers have had their fill, the remaining fresh water is fed to the ship's potable water systems for drinking, showers, hand washing, cooking, etc. All of the urinals and all but one of the toilets on the Iowa class flush with salt water in order to conserve fresh water. The turbines, especially the HP turbine, can turn at 2,000 rpm; their shafts drive through reduction gearing that turns the propeller shafts at speeds up to 225 rpm, depending upon the desired speed of the ship.[65] The Iowas were outfitted with four screws: the outboard pair consisting of four-bladed propellers 18.25 ft (5.56 m) in diameter and the inboard pair consisting of five-bladed propellers 17 ft (5.18 m) in diameter. The propeller designs were adopted after earlier testing had determined that propeller cavitation caused a drop in efficiency at speeds over 30 kn (56 km/h; 35 mph). The two inner shafts were housed in skegs to smooth the flow of water to the propellers and improve the structural strength of the stern.[66]

Each of the four engine rooms has a pair of 1,250 kW Ship's Service Turbine Generators (SSTGs), providing the ship with a total non-emergency electrical power of 10,000 kW at 450 volts alternating current. Additionally, the vessels have a pair of 250 kW emergency diesel generators.[25] To allow battle-damaged electrical circuits to be repaired or bypassed, the lower decks of the ship have a Casualty Power System whose large 3-wire cables and wall outlets called "biscuits" can be used to reroute power.[67]

Electronics (1943–69)

[edit]The earliest search radars installed were the SK air-search radar and SG surface-search radar during World War II. They were located on the mainmast and forward fire-control tower of the battleships, respectively. As the war drew to a close, the United States introduced the SK-2 air-search radar and SG surface-search radar; the Iowa class was updated to make use of these systems between 1945 and 1952. At the same time, the ships' radar systems were augmented with the installation of the SP height finder on the main mast. In 1952, AN/SPS-10 surface-search radar and AN/SPS-6 air-search radar replaced the SK and SG radar systems, respectively. Two years later the SP height finder was replaced by the AN/SPS-8 height finder, which was installed on the main mast of the battleships.[68]

In addition to these search and navigational radars, the Iowa class were also outfitted with a variety of fire control radars for their gun systems. Beginning with their commissioning, the battleships made use of a pair of Mk 38 gun fire control systems with Mark 8 fire control radar to direct the 16-inch guns and a quartet of Mk 37 gun fire control systems with Mark 12 fire control radar and Mark 22 height finding radar to direct the 5-inch gun batteries. These systems were upgraded over time with the Mark 13 replacing the Mark 8 and the Mark 25 replacing the Mark 12/22, but they remained the cornerstones of the combat radar systems on the Iowa class during their careers.[69] The range estimation of these gunfire control systems provided a significant accuracy advantage over earlier ships with optical rangefinders; this was demonstrated off Truk Atoll on 16 February 1944, when the New Jersey engaged the Japanese destroyer Nowaki at a range of 35,700 yards (32.6 km; 17.6 nmi) and straddled her, setting the record for the longest-ranged straddle in history.[37]

In World War II, the electronic countermeasures (ECM) included the SPT-1 and SPT-4 equipment; passive electronic support measures (ESM) were a pair of DBM radar direction finders and three intercept receiving antennas, while the active components were the TDY-1 jammers located on the sides of the fire control tower. The ships were also equipped with the identification, friend or foe (IFF) Mark III system, which was replaced by the IFF Mark X when the ships were overhauled in 1955. When the New Jersey was reactivated in 1968 for the Vietnam War, she was outfitted with the ULQ-6 ECM system.[70]

Armor

[edit]

Like all battleships, the Iowas carried heavy armor protection against shellfire and bombs with significant underwater protection against torpedoes. The Iowas' "all-or-nothing" armor scheme was largely modeled on that of the preceding South Dakota class, and designed to give a zone of immunity against fire from 16-inch/45-caliber guns between 18,000 and 30,000 yards (16,000 and 27,000 m; 10 and 17 mi) away. The protection system consists of Class A face-hardened Krupp cemented (K.C.) armor and Class B homogeneous Krupp-type armor; furthermore, special treatment steel (STS), a high-tensile structural steel with armor properties comparable to Class B, was extensively used in the hull plating to increase protection.[71]

The citadel consisting of the magazines and engine rooms was protected by an STS outer hull plating 1.5 inches (38 mm) thick and a Class A armor belt 12.1 inches (307 mm) thick mounted on 0.875-inch (22.2 mm) STS backing plate; the armor belt is sloped at 19 degrees, equivalent to 17.3 in (439 mm) of vertical class B armor at 19,000 yards. The armor belt extends to the triple bottom, where the Class B lower portion tapers to 1.62 inches (41 mm). The ends of the armored citadel are closed by 11.3-inch (287 mm) vertical Class A transverse bulkheads for Iowa and New Jersey. The transverse bulkhead armor on Missouri and Wisconsin was increased to 14.5 inches (368 mm); this extra armor provided protection from raking fire directly ahead, which was considered more likely given the high speed of the Iowas. The deck armor consists of a 1.5-inch-thick (38 mm) STS weather deck, a combined 6-inch-thick (152 mm) Class B and STS main armor deck, and a 0.63-inch-thick (16 mm) STS splinter deck. Over the magazines, the splinter deck is replaced by a 1-inch (25 mm) STS third deck that separates the magazine from the main armored deck.[72] The powder magazine rooms are separated from the turret platforms by a pair of 1.5-inch STS annular bulkheads under the barbettes for flashback protection.[72] The installation of armor on the Iowas also differed from those of earlier battleships in that the armor was installed while the ships were still "on the way" rather than after the ships had been launched.[73]

The Iowas had heavily protected main battery turrets, with 19.5-inch (495 mm) Class B and STS face, 9.5-inch (241 mm) Class A sides, 12-inch (305 mm) Class A rear, and 7.25-inch (184 mm) Class B roof. The turret barbettes' armor is Class A with 17.3 inches (439 mm) abeam and 11.6 inches (295 mm) facing the centerline, extending down to the main armor deck. The conning tower armor is Class B with 17.3 inches (439 mm) on all sides and 7.25 inches (184 mm) on the roof. The secondary battery turrets and handling spaces were protected by 2.5 inches (64 mm) of STS. The propulsion shafts and steering gear compartment behind the citadel had considerable protection, with 13.5-inch (343 mm) Class A side strake and 5.6–6.2-inch (142–157 mm) roof.[72][30]

The armor's immunity zone shrank considerably against guns equivalent to their own 16-inch/50-caliber guns armed with the Mk 8 armor-piercing shell due to the weapon's increased muzzle velocity and improved shell penetration; increasing the armor would have increased weight and reduced speed, a compromise that the General Board was not willing to make.[72]

The Iowas' torpedo defense was based on the South Dakotas' design, with modifications to address shortcomings discovered during caisson tests. The system is an internal "bulge" that consists of four longitudinal torpedo bulkheads behind the outer hull plating with a system depth of 17.9 feet (5.46 m) to absorb the energy of a torpedo warhead. The extension of the armor belt to the triple bottom, where it tapers to a thickness of 1.62 inches (41 mm), serves as one of the torpedo bulkheads and was hoped to add to protection; the belt's lower edge was welded to the triple bottom structure and the joint was reinforced with buttstraps due to the slight knuckle causing a structural discontinuity. The torpedo bulkheads were designed to elastically deform to absorb energy and the two outer compartments were liquid loaded in order to disrupt the gas bubble and slow fragments. The outer hull was intended to detonate a torpedo, with the outer two liquid compartments absorbing the shock and slowing any splinters or debris while the lower armored belt and the empty compartment behind it absorb any remaining energy. However, the Navy discovered in caisson tests in 1939 that the initial design for this torpedo defense system was actually less effective than the previous design used on the North Carolinas due to the rigidity of the lower armor belt causing the explosion to significantly displace the final holding bulkhead inwards despite remaining watertight. To mitigate the effects, the third deck and triple bottom structure behind the lower armor belt were reinforced and the placement of brackets was changed.[74][75] Iowas' system was also improved over the South Dakotas' through closer spacing of the transverse bulkheads, greater thickness of the lower belt at the triple bottom joint, and increased total volume of the "bulge".[76][77] The system was further modified for the last two ships of the class, Illinois and Kentucky, by eliminating knuckles along certain bulkheads; this was estimated to improve the strength of the system by as much as 20%.[78]

Based on costly lessons in the Pacific theater, concerns were raised about the ability of the armor on these battleships to withstand aerial bombing, particularly high-altitude bombing using armor-piercing bombs. Developments such as the Norden bombsight further fueled these concerns. While the design of the Iowas was too far along to adequately address this issue, experience in the Pacific theater eventually demonstrated that high-altitude unguided bombing was ineffective against maneuvering warships.[79]

Aircraft (1943–69)

[edit]When they were commissioned during World War II, the Iowa-class battleships came equipped with two aircraft catapults designed to launch floatplanes. Initially, the Iowas carried the Vought OS2U Kingfisher[80] and Curtiss SC Seahawk,[80][81] both of which were employed to spot for the battleship's main gun batteries – and, in a secondary capacity, perform search-and-rescue missions.

By the time of the Korean War, helicopters had replaced floatplanes and the Sikorsky HO3S-1 helicopter was employed.[80] New Jersey made use of the Gyrodyne QH-50 DASH drone for her Vietnam War deployment in 1968–69.[82]

Conversion proposals

[edit]The Iowa class were the only battleships with the speed required for post-war operations based around fast aircraft carrier task forces.[83] There were several proposals in the early Cold War to convert the class to take into account changes in technology and doctrine. These included plans to equip the class with nuclear missiles, add aircraft capability, and – in the case of Illinois and Kentucky – a proposal to rebuild both as aircraft carriers instead of battleships.[84][85]

Initially, the Iowa class was to consist of only four battleships with hull numbers BB-61 to BB-64: Iowa, New Jersey, Missouri, and Wisconsin. However, changing priorities during World War II resulted in the battleship hull numbers BB-65 Montana and BB-66 Ohio being reordered as Illinois and Kentucky, respectively; Montana and Ohio were reassigned to hull numbers BB-67 and BB-68. At the time these two battleships were to be built a proposal was put forth to have them constructed as aircraft carriers rather than fast battleships. The plan called for the ships to be rebuilt to include a flight deck and an armament suite similar to that placed aboard the Essex-class aircraft carriers that were at the time under construction in the United States.[84][85] Ultimately, nothing came of the design proposal to rebuild these two ships as aircraft carriers and they were cleared for construction as fast battleships to conform to the Iowa-class design, though they differed from the earlier four that were built. Eventually, the Cleveland-class light cruisers were selected for the aircraft-carrier conversion. Nine of these light cruisers would be rebuilt as Independence-class light aircraft carriers.[86]

After the surrender of the Empire of Japan, construction on Illinois and Kentucky stopped. Illinois was eventually scrapped, but Kentucky's construction had advanced enough that several plans were proposed to complete Kentucky as a guided missile battleship (BBG) by removing the aft turret and installing a missile system.[87][20] A similar conversion had already been performed on the battleship Mississippi (BB-41/AG-128) to test the RIM-2 Terrier missile after World War II.[88] One such proposal came from Rear Admiral W.K. Mendenhall, Chairman of the Ship Characteristics Board (SCB); Mendenhall proposed a plan that called for $15–30 million to be spent to allow Kentucky to be completed as a guided-missile battleship (BBG) carrying eight SSM-N-8 Regulus II guided missiles with a range of 1,000 nautical miles (1,900 km; 1,200 mi). He also suggested Terrier or RIM-8 Talos launchers to supplement the AA guns and proposed nuclear (instead of conventional) shells for the 16-inch guns.[89] This never materialized,[90] and Kentucky was ultimately sold for scrap in 1958, although her bow was used to repair her sister Wisconsin after a collision on 6 May 1956, earning her the nickname WisKy.[87]

In 1954, the Long Range Objectives Group of the United States Navy suggested converting the Iowa-class ships to BBGs. In 1958, the Bureau of Ships offered a proposal based on this idea. This replaced the 5- and 16-inch gun batteries with "two Talos twin missile systems, two RIM-24 Tartar twin missile systems, an RUR-5 ASROC antisubmarine missile launcher, and a Regulus II installation with four missiles",[91] as well as flagship facilities, sonar, helicopters, and fire-control systems for the Talos and Tartar missiles. In addition to these upgrades, 8,600 long tons (8,700 t) of additional fuel oil was also suggested to serve in part as ballast for the battleships and for use in refueling destroyers and cruisers. Due to the estimated cost of the overhaul ($178–193 million) this proposal was rejected as too expensive; instead, the SCB suggested a design with one Talos, one Tartar, one ASROC, and two Regulus launchers and changes to the superstructure, at a cost of up to $85 million. This design was later revised to accommodate the Polaris Fleet Ballistic Missile, which in turn resulted in a study of two schemes by the SCB. In the end, none of these proposed conversions for the battleships were ever authorized.[92] Interest in converting the Iowas into guided-missile battleships began to deteriorate in 1960 because the hulls were considered too old and the conversion costs too high.[93] Nonetheless, additional conversion proposals – including one to install the AN/SPY-1 Aegis Combat System radar[90] on the battleships – were suggested in 1962, 1974, and 1977, but as before, these proposals failed to gain the needed authorization.[94] This was due, in part, to the possibility that sensitive electronics within 200 ft (61 m) of any 16-inch gun muzzle may be damaged from overpressure.[93]

1980s reactivation/modernization

[edit]

In 1980, Ronald Reagan was elected president on a promise to build up the US military as a response to the increasing military power of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Navy was commissioning the Kirov class of missile cruisers, the largest type of surface combatant since World War II. As part of Reagan's 600-ship Navy policy and as a counter to the Kirov class, the US Navy began reactivating the four Iowa-class units and modernizing them for service.[95]

The Navy considered several proposals that would have removed the aft 16-inch turret. Martin Marietta proposed to replace the turret with servicing facilities for 12 AV-8B Harrier STOVL jump jets. Charles Myers, a former Navy test pilot turned Pentagon consultant, proposed replacing the turret with vertical launch systems for missiles and a flight deck for Marine helicopters. In July 1981, the US Naval Institute's Proceedings published a proposal by naval architect Gene Anderson for a canted flight deck with steam catapult and arrestor wires for F/A-18 Hornet fighters.[96] Plans for these conversions were dropped in 1984.[97]

Each battleship was overhauled to burn navy distillate fuel and modernized to carry electronic warfare suites, close-in weapon systems (CIWS) for self-defense, and missiles. The obsolete electronics and anti-aircraft armament were removed to make room for more modern systems. The Navy spent about $1.7 billion, from 1981 through 1988, to modernize and reactivate the four Iowa-class battleships,[98] roughly the same as building four Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates.

After modernization, the full load displacement was relatively unchanged at 57,500 long tons (58,400 t).[99]

The modernized battleships operated as centerpieces of their own battle group (termed as a Battleship Battle Group or Surface Action Group), consisting of one Ticonderoga-class cruiser, one Kidd-class destroyer or Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, one Spruance-class destroyer, three Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates and one support ship, such as a fleet oiler.[100]

Armament

[edit]During their modernization in the 1980s, each Iowa was equipped with four of the US Navy's Phalanx CIWS mounts, two of which sat just behind the bridge and two which were next to the ship's aft funnel. Iowa, New Jersey, and Missouri were equipped with the Block 0 version of the Phalanx, while Wisconsin received the first operational Block 1 version in 1988.[101] The Phalanx system is intended to serve as a last line of defense against enemy missiles and aircraft, and when activated can engage a target with a 20 mm M61 Vulcan 6-barreled Gatling cannon[102] at a distance of approximately 4,000 yards (3.7 km; 2.0 nmi).[101]

As part of their modernization in the 1980s, each of the Iowas received a complement of eight quad-cell Armored Box Launchers and four "shock hardened" Mk 141 quad-cell launchers. The former was used by the battleships to carry and fire the BGM-109 Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAMs) for use against enemy targets on land, while the latter system enabled the ships to carry a complement of RGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles for use against enemy ships. With an estimated range of 675 to 1,500 nautical miles (1,250 to 2,778 km; 777 to 1,726 mi)[103] for the Tomahawks and 64.5 to 85.5 nautical miles (119.5 to 158.3 km; 74.2 to 98.4 mi)[103] for the Harpoons, these two missile systems displaced the 16-inch guns and their maximum range of 42,345 yards (38.7 km; 20.9 nmi)[36] to become the longest-ranged weapons on the battleships during the 1980s; the ships' complement of 32 Tomahawk missiles was the largest until the Mk 41 VLS-equipped Ticonderoga-class cruisers entered service. It has been alleged by members of the environmental group Greenpeace[104] that the battleships carried the TLAM-A (also cited, incorrectly, as the TLAM-N) – a Tomahawk missile with a variable yield W80 nuclear warhead – during their 1980s service with the United States Navy, but owing to the United States Navy's policy of refusing to confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weaponry aboard its ships, these claims can not be conclusively proved.[45][N 7] Between 2010 and 2013, the US withdrew the BGM-109A, leaving only conventional munitions packages for its Tomahawk missile inventory, though the Iowas had been withdrawn from service at that point.[105]

Owing to the original 1938 design of the battleships, the Tomahawk missiles could not be fitted to the Iowa class unless the battleships were rebuilt in such a way as to accommodate the missile mounts that would be needed to store and launch the Tomahawks. This realization prompted the removal of the anti-aircraft guns previously installed on the Iowas and the removal of four of each of the battleships' ten 5-inch/38 DP mounts. The mid and aft end of the battleships were then rebuilt to accommodate the missile launchers. At one point, the NATO Sea Sparrow was to be installed on the reactivated battleships; however, it was determined that the system could not withstand the overpressure effects of firing the main battery.[106] To supplement the anti-aircraft capabilities of the Iowas, five FIM-92 Stinger surface-to-air missile firing positions were installed. These secured the shoulder-launched weapons and their rounds for ready use by the crew.[103]

Electronics

[edit]During their modernization under the 600-ship Navy program, the Iowa-class battleships' radar systems were again upgraded. The foremast was of a new tripod design that was considerably reinforced to allow the AN/SPS-6 air-search radar system to be replaced with the AN/SPS-49 radar set (which also augmented the existing navigation capabilities on the battleships), and the AN/SPS-8 surface-search radar set was replaced by the AN/SPS-67 search radar. The new mast also incorporates a Tactical Air Navigation System (TACAN) antenna.[80] The aft mast was changed to be placed in front of the aft funnel and mounts a circular SATCOM antenna while another one was mounted on the fire control mast.[107]

By the Korean War, jet engines had replaced propellers on aircraft, which severely limited the ability of the 20 mm and 40 mm AA batteries and their gun systems to track and shoot down enemy planes. Consequently, the AA guns and their associated fire-control systems were removed when reactivated. New Jersey received this treatment in 1967, and the others followed in their 1980s modernizations. In the 1980s, each ship also received a quartet of Phalanx CIWS mounts which made use of a radar system to locate incoming enemy projectiles and destroy them with a 20 mm Gatling gun before they could strike the ship.[69][108]

With the added missile capacity of the battleships in the 1980s came additional fire-support systems to launch and guide the ordnance. To fire the Harpoon anti-ship missiles, the battleships were equipped with the SWG-1 fire-control system, and to fire the Tomahawk missiles the battleships used either the SWG-2 or SWG-3 fire-control system. In addition to these offensive-weapon systems, the battleships were outfitted with the AN/SLQ-25 Nixie to be used as a lure against enemy torpedoes; an SLQ-32 electronic warfare system that can detect, jam, and deceive an opponent's radar; and a Mark 36 SRBOC system to fire chaff rockets intended to confuse enemy missiles.[69][108]

Aside from the electronics added for weaponry control, all four battleships were outfitted with a communications suite used by both cruisers and guided missile cruisers in service at the time.[90] This communication suite included the OE-82 antenna for satellite communications[109] but did not include the Naval Tactical Data System.[90]

Aircraft (1982–1992)

[edit]

During the 1980s these battleships made use of the RQ-2 Pioneer, an unmanned aerial vehicle employed in spotting for the guns. Launched from the fantail using a rocket-assist booster that was discarded shortly after takeoff, the Pioneer carried a video camera in a pod under the belly of the aircraft which transmitted live video to the ship so operators could observe enemy actions or fall of shot during naval gunnery. To land the UAV a large net was deployed at the back of the ship; the aircraft was flown into it. Missouri and Wisconsin both used the Pioneer UAVs successfully during Operation Desert Storm, and in one particularly memorable incident,[110] a Pioneer UAV operated by Wisconsin received the surrender of Iraqi troops during combat operations.[110] This particular Pioneer was later donated to the Smithsonian Institution and is now on public display.[111] During Operation Desert Storm these Pioneers were operated by detachments of VC-6.[112] In addition to the Pioneer UAVs, the recommissioned Iowas could support six types of helicopters: the Sikorsky HO3S-1,[80] UH-1 Iroquois, SH-2 Seasprites, CH-46 Sea Knight, CH-53 Sea Stallion, and LAMPS III SH-60B Seahawk.

Gunfire support role

[edit]Following the 1991 Gulf War and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union, the United States Navy began to decommission and mothball many of the ships it had brought out of its reserve fleet in the drive to attain a 600-ship Navy. At the height of Navy Secretary John F. Lehman's 600-ship Navy plan, nearly 600 ships of all types were active within the Navy. This included fifteen aircraft carriers, four battleships, and over 100 submarines, along with various other types of ships the overall plan specified. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 the Navy sought to return to its traditional, 313-ship composition.[113] While reducing the fleet created under the 600-ship Navy program, the decision was made to deactivate the four recommissioned Iowa-class battleships and return them to the reserve fleet.[N 11]

In 1995, the decommissioned battleships were removed from the Naval Vessel Register after it was determined by ranking US Navy officials that there was no place for a battleship in the modern navy.[82] In response to the striking of the battleships from the Naval Vessel Register a movement began to reinstate the battleships, on the grounds that these vessels had superior firepower over the 5-inch guns found on the Spruance, Kidd and Arleigh Burke-class destroyers and Ticonderoga-class cruisers.[115] Citing concern over the lack of available gunfire to support amphibious operations, Congress required the Navy to reinstate two battleships to the Naval Vessel Register[82] and maintain them with the mothball fleet, until the Navy could certify it had gunfire support within the current fleet that would meet or exceed the battleship's capability.[116]

The debate over battleships in the modern navy continued until 2006, when the two reinstated battleships were stricken after naval officials submitted a two-part plan that called for the near-term goal of increasing the range of the guns in use on the Arleigh Burke-class destroyers with new Extended Range Guided Munition (ERGM) ammunition intended to allow a 5-inch projectile fired from these guns to travel an estimated 40 nautical miles (74 km; 46 mi) inland.[117][118] The long-term goal called for the replacement of the two battleships with 32 vessels of the Zumwalt class of guided-missile destroyers. Cost overruns caused the class to be reduced to three ships. These ships are outfitted with an Advanced Gun System (AGS) that was to fire specially developed 6-inch Long Range Land Attack Projectiles for shore bombardment.[119] LRLAP procurement was canceled in 2017 and the AGS is unusable. The long-term goal for the Zumwalt class is to have the ships mount railguns[120] or free-electron lasers.[121][N 12]

Cultural significance

[edit]

The Iowa class became culturally symbolic in the United States in many different ways, to the point where certain elements of the American public – such as the United States Naval Fire Support Association – were unwilling to part with the battleships, despite their apparent obsolescence in the face of modern naval combat doctrine that places great emphasis on air supremacy and missile firepower. Although all were officially stricken from the Naval Vessel Register they were spared scrapping and were donated for use as museum ships.[123][124][125][126]

Their service records added to their fame, ranging from their work as carrier escorts in World War II to their shore bombardment duties in North Korea, North Vietnam, and the Middle East, as well as their service in the Cold War against the expanded Soviet Navy.[N 13] Their reputation combined with the stories told concerning the firepower of these battleships' 16-inch guns[129] were such that when they were brought out of retirement in the 1980s in response to increased Soviet Naval activity – and in particular, in response to the commissioning of the Kirov-class battlecruisers[95] – the United States Navy was inundated with requests from former sailors pleading for a recall to active duty so they could serve aboard one of the battleships.[130]

In part because of the service length and record of the class, members have made numerous appearances in television shows, video games, movies, and other media, including appearances of the Kentucky and Illinois in the anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion,[131] the History Channel documentary series Battle 360: USS Enterprise,[132] the Discovery Channel documentary The Top 10 Fighting Ships (where the Iowa class was rated Number 1),[133] the book turned movie A Glimpse of Hell,[134][135] the 1989 music video for the song by Cher "If I Could Turn Back Time",[136] the 1992 film Under Siege,[137] the 2012 film Battleship,[138] among other appearances. Japanese rock band Vamps performed the finale of their 2009 US tour on board Missouri on 19 September 2009.[139]

Ships in class

[edit]

When brought into service during the final years of World War II, the Iowa-class battleships were assigned to operate in the Pacific Theatre of World War II. By this point in the war, aircraft carriers had displaced battleships as the primary striking arm of both the United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy. As a result of this shift in tactics, US fast battleships of all classes were relegated to the secondary role of carrier escorts and assigned to the Fast Carrier Task Force to provide anti-aircraft screening for Allied aircraft carriers and perform shore bombardment.[140] Three were recalled to service in the 1950s with the outbreak of the Korean War,[N 14] and they provided naval artillery support for U.N. forces for the entire duration of the war before being returned to mothballs in 1955 after hostilities ceased. In 1968, to help alleviate US air losses over North Vietnam,[141] New Jersey was summoned to Vietnam, but she was decommissioned a year after arriving.[142] All four returned in the 1980s during the drive for a 600-ship Navy to counter the new Soviet Kirov-class battlecruisers,[95] only to be retired after the collapse of the Soviet Union on the grounds that they were too expensive to maintain.[114][N 15]

| Ship name | Hull no. | Builder | Ordered | Laid down | Launched | Comm./ |

Decomm. | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iowa | BB-61 | Brooklyn Navy Yard, New York City | 1 July 1939 | 27 June 1940 | 27 August 1942 | 22 February 1943 | 24 March 1949 | Preserved as museum ship in Los Angeles, California |

| 25 August 1951 | 24 February 1958 | |||||||

| 28 April 1984 | 26 October 1990 | |||||||

| New Jersey | BB-62 | Navy Yard, Philadelphia | 16 September 1940 | 7 December 1942 | 23 May 1943 | 30 June 1948 | Preserved as museum ship in Camden, New Jersey | |

| 21 November 1950 | 21 August 1957 | |||||||

| 6 April 1968 | 17 December 1969 | |||||||

| 28 December 1982 | 8 February 1991 | |||||||

| Missouri | BB-63 | Brooklyn Navy Yard, New York City | 12 June 1940 | 6 January 1941 | 29 January 1944 | 11 June 1944 | 26 February 1955 | Preserved as museum ship in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii |

| 10 May 1986 | 1 March 1992 | |||||||

| Wisconsin | BB-64 | Navy Yard, Philadelphia | 25 January 1941 | 7 December 1943 | 16 April 1944 | 1 July 1948 | Preserved as museum ship in Norfolk, Virginia | |

| 3 March 1951 | 8 March 1958 | |||||||

| 22 October 1988 | 30 September 1991 | |||||||

| Illinois | BB-65 | 9 September 1940 | 6 December 1942 | — | — | — | Canceled 11 August 1945 Broken up at Philadelphia, 1958 | |

| Kentucky | BB-66 | Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth | 7 March 1942 | 20 January 1950[a] | — | — | Broken up at Baltimore, 1959 | |

| BBG-1 |

Iowa

[edit]

Iowa was ordered 1 July 1939, laid down 27 June 1940, launched 27 August 1942, and commissioned 22 February 1943. She conducted a shakedown cruise in Chesapeake Bay before sailing to Naval Station Argentia, Newfoundland, to be ready in case the German battleship Tirpitz entered the Atlantic.[143] Transferred to the Pacific Fleet in 1944, Iowa made her combat debut in February and participated in the campaign for the Marshall Islands.[144] The ship later escorted US aircraft carriers conducting air raids in the Marianas campaign, and then was present at the Battle of Leyte Gulf.[144] During the Korean War, Iowa bombarded enemy targets at Songjin, Hŭngnam and Kojo, North Korea. Iowa returned to the US for operational and training exercises before being decommissioned on 24 February 1958.[145] Reactivated in the early 1980s, Iowa operated in the Atlantic Fleet, cruising in North American and European waters for most of the decade and participating in joint military exercises with European ships.[146] On 19 April 1989, 47 sailors were killed following an explosion in her No. 2 turret.[147] In 1990, Iowa was decommissioned for the last time and placed in the mothball fleet. She was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 17 March 2006. Iowa was anchored as part of the National Defense Reserve Fleet in Suisun Bay, California until October 2011, when she was towed from her mooring to Richmond, California for renovation as a museum ship. She was towed from Richmond in the San Francisco Bay on 26 May 2012, to San Pedro at the Los Angeles Waterfront to serve as a museum ship run by Pacific Battleship Center and opened to the public on 7 July 2012.

New Jersey

[edit]

New Jersey was ordered 4 July 1939, laid down 16 September 1940, launched 7 December 1942, and commissioned 23 May 1943. New Jersey completed fitting out and trained her initial crew in the Western Atlantic and Caribbean before transferring to the Pacific Theatre in advance of the planned assault on the Marshall Islands, where she screened the US fleet of aircraft carriers from enemy air raids. At the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the ship protected carriers with her anti-aircraft guns. New Jersey then bombarded Iwo Jima and Okinawa. During the Korean War, the ship pounded targets at Wonsan, Yangyang, and Kansong. Following the Armistice, New Jersey conducted training and operation cruises until she was decommissioned on 21 August 1957. Recalled to duty in 1968, New Jersey reported to the gunline off the Vietnamese coast and shelled North Vietnamese targets before departing the line in December 1968.[148] She was decommissioned the following year.[149] Reactivated in 1982 under the 600-ship Navy program,[150] New Jersey was sent to Lebanon to protect US interests and US Marines, firing her main guns at Druze and Syrian positions in the Beqaa Valley east of Beirut.[151] Decommissioned for the last time 8 February 1991, New Jersey was briefly retained on the Naval Vessel Register before being donated to the Home Port Alliance of Camden, New Jersey for use as a museum ship in October 2001.[152]

Missouri

[edit]

Missouri was the last of the four Iowas to be completed. She was ordered 12 June 1940, laid down 6 January 1941, launched 29 January 1944, and commissioned 11 June 1944. Missouri conducted her trials off New York with shakedown and battle practice in the Chesapeake Bay before transferring to the Pacific Fleet, where she screened US aircraft carriers involved in offensive operations against the Japanese before reporting to Okinawa to shell the island in advance of the planned landings. Following the bombardment of Okinawa, Missouri turned her attention to the Japanese homeland islands of Honshu and Hokkaido, performing shore bombardment and screening US carriers involved in combat operations. She became a symbol of the US Navy's victory in the Pacific when representatives of the Empire of Japan boarded the battleship to sign the documents of unconditional surrender to the Allied powers in September 1945. After World War II, Missouri conducted largely uneventful training and operational cruises until suffering a grounding accident. In 1950, she was dispatched to Korea in response to the outbreak of the Korean War. Missouri served two tours of duty in Korea providing shore bombardment. She was decommissioned in 1956. She spent many years at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington. Reactivated in 1984, as part of the 600-ship Navy plan, Missouri was sent on operational cruises until being assigned to Operation Earnest Will in 1988. In 1991, Missouri participated in Operation Desert Storm, firing 28 Tomahawk Missiles and 759 16-inch shells at Iraqi targets along the coast.[153] Decommissioned for the last time in 1992, Missouri was donated to the USS Missouri Memorial Association of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, for use as a museum ship in 1999.[154]

Wisconsin

[edit]

Wisconsin was ordered 12 June 1940, laid down 25 January 1942, launched 7 December 1943, and commissioned 16 April 1944. After trials and initial training in the Chesapeake Bay, she transferred to the Pacific Fleet in 1944 and was assigned to protect the US fleet of aircraft carriers involved in operations in the Philippines until summoned to Iwo Jima to bombard the island in advance of the Marine landings. Afterward, she proceeded to Okinawa, bombarding the island in advance of the Allied amphibious assault. In mid-1945 Wisconsin turned her attention to bombarding the Japanese home islands until the surrender of Japan in August. Reactivated in 1950, for the Korean War, Wisconsin served two tours of duty, assisting South Korean and UN forces by providing call fire support and shelling targets. In 1956, the bow of the uncompleted Kentucky was removed and grafted on Wisconsin, which had collided with the destroyer USS Eaton.[155] Decommissioned in 1958, Wisconsin was placed in the reserve fleet at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard until reactivated in 1986 as part of the 600-ship Navy plan.[156] In 1991, Wisconsin participated in Operation Desert Storm, firing 24 Tomahawk Missiles at Iraqi targets and expending 319 16-inch shells[148] at Iraqi troop formations along the coast. Decommissioned for the last time 30 September 1991, Wisconsin was placed in the reserve fleet until stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 17 March 2006, so she could be transferred for use as a museum ship. Wisconsin is currently berthed at the Nauticus maritime museum in Norfolk, Virginia.[156]

Illinois and Kentucky

[edit]

Hull numbers BB-65 and BB-66 were originally intended as the first and second ships of the Montana-class of battleships;[157] however, the passage of an emergency war building program on 19 July 1940 resulted in both hulls being reordered as Iowa-class units to save time on construction.[158] The war ended before either could be completed, and work was eventually stopped. Initially, proposals were made to convert the hulls into aircraft carriers similar to the Essex class, but the effort was dropped.[159]

Illinois was ordered on 9 September 1940 and initially laid down on 6 December 1942. However, work was suspended pending a decision on whether to convert the hull to an aircraft carrier. Upon determination the result would cost more and be less capable than building from scratch, construction resumed, but it was canceled for good approximately one-quarter complete on 11 August 1945.[160] She was sold for scrap and broken up on the slipway in September 1958.[161][162]

Kentucky was ordered on 9 September 1940 and laid down on 7 March 1942. Work on the ship was suspended in June 1942, and the hull floated out to make room for the construction of LSTs.[163] The interruption lasted for two and a half years while a parallel aircraft carrier debate played out as with Illinois, reaching the same conclusion. Work resumed in December 1944, with completion projected for mid-1946. Further suggestions were made to convert Kentucky into a specialist anti-aircraft ship, and work was again suspended. With the hull approximately three-quarters completed, she was floated on 20 January 1950, to clear a dry dock for repairs to Missouri, which had run aground. During this period, plans were proposed to convert Kentucky into a guided missile battleship, which saw her reclassified from BB-66 to BBG-1.[164] When these failed construction of any sort, work never resumed and the ship was used as a parts hulk; in 1956, her bow was removed and shipped in one piece across Hampton Roads and grafted onto Wisconsin, which had collided with the destroyer Eaton.[156] In 1958, the engines installed on Kentucky were salvaged and installed on the Sacramento-class fast combat support ships Sacramento and Camden.[157] Ultimately, what remained of the hulk was sold for scrap on 31 October 1958.[145]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Standard displacement, also known as "Washington displacement", is a specific term defined by the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. It is the displacement of the ship complete, fully manned, engined, and equipped ready for sea, including all armament and ammunition, equipment, outfit, provisions and fresh water for crew, miscellaneous stores, and implements of every description that are intended to be carried in war, but without fuel or reserve boiler feed water on board.[7]

- ^ Also considered was the 16-inch/56 caliber gun, but this was dropped in March 1938 due to the weapon's weight.[9]

- ^ The belt armor was increased from 8.1 inches (206 mm) to 12.6 inches (320 mm); the deck armor from 2.3 inches (58 mm) to 5 inches (127 mm); the splinter armor to 3.9 inches (99 mm); the turret armor from 9 inches (229 mm) on the front, 6 inches (152 mm) on the side, and 5 inches on the rear to 18 inches (457 mm), 10 inches (254 mm) and 8 inches (203 mm), respectively.[14]

- ^ Individual ship's dimensions vary slightly from design values. Iowa is 859 ft 5+3⁄4 in (261.969 m) waterline length, 887 ft 2+3⁄4 in (270.427 m) overall length, and 108 ft 2+1⁄16 in (32.971 m) beam. New Jersey is 859 ft 10+1⁄4 in (262.084 m) waterline length, 887 ft 6+5⁄8 in (270.526 m) overall length, and 108 ft 1+3⁄8 in (32.953 m) beam.[28][29]

- ^ These mathematical formulas still stand today, and they have been used to design hulls for US ships and to predict the speed of those hulls for the ships when commissioned, including nuclear-powered ships like the US fleet of Nimitz-class supercarriers.[31]

- ^ a b The actual range of the Iowa-class battleship's 16"/50 caliber guns varies from source to source. The most commonly cited distance for the 16"/50 caliber gun is approximately 20 miles; however, this number does not necessarily take into consideration the age of the gun barrel, the gun barrel's elevation, the projectile variant (armor piercing or high explosive), or the powder charges required to launch the artillery shell, all of which affect the range that a shell fired from a 16"/50 caliber gun can attain. The longest confirmed shot fired against an enemy naval unit using a 16"/50 caliber gun appears to have occurred during the raid against Imperial Japanese Navy units at Truk Atoll, when Iowa straddled a destroyer at 35,700 yards,[37] while the longest shot ever fired by a 16"/50 caliber gun in a non-combat situation is alleged to have occurred during an unauthorized naval gunnery experiment conducted 20 January 1989 off the coast of Vieques, Puerto Rico by Iowa's Master Chief Fire Controlman, Stephen Skelley, and Gunnery Officer, Lieutenant Commander Kenneth Michael Costigan, who claimed that one of the 16-inch shells traveled 23.4 nautical miles (40 km).[failed verification] In addition, the standard 20-mile range does not take into account experimental artillery shells that were under consideration for use with the 16"/50 caliber gun in the 1980s, some of which are alleged to have been capable of traveling distances in excess of the often cited 20-mile gun range. One example is the Improved HC shell, which is said to have been test fired from Iowa at Dahlgren sometime after her 1980s recommissioning and is alleged to have achieved a range of over 51,000 yards.[36]

- ^ a b "Military members and civilian employees of the Department of the Navy shall not reveal, report to reveal, or cause to be revealed any information, rumor, or speculation with respect to the presence or absence of nuclear weapons or components aboard any specific ship, station or aircraft, either on their own initiative or in response, direct or indirect, to any inquiry. [...] The Operations Coordinating Board (part of President Eisenhower's National Security Council) established the US policy in 1958 of neither confirming nor denying (NCND) the presence or absence of nuclear weapons at any general or specific location, including aboard any US military station, ship, vehicle, or aircraft."[46]

- ^ In early 1945, the United States Navy determined that these 40 mm guns were also inadequate for defense against Japanese kamikaze attacks in the Pacific Theater, and subsequently began to replace the Bofors guns with a 3-inch (76 mm)/50 caliber gun capable of using variable time (VT) charges.[54][55]

- ^ "As part of their modernizations, the Iowa-class vessels lost their AA batteries in favor of Phalanx Close-In Weapon Systems and several of their 5-inch/38cal guns to make room for the launchers for the TLAMs and Harpoons."[57]

- ^ The empirical formula permitted a theoretical maximum speed of 34.9 kn (64.6 km/h; 40.2 mph). However, the actual maximum speed of the Iowa-class battleships was never verified during World War II as the ships never ran a measured mile at full power; 31 kn (57.4 km/h; 35.7 mph) was considered the operating speed when bottom fouling and sea state were taken into account.[60] During 1985 sea trials, Iowa achieved 31.0 kn (57.4 km/h; 35.7 mph) at 186,260 shp (138,890 kW) and nearly full load displacement of 55,960 long tons (56,860 t).[61][62] When lightly loaded, New Jersey achieved 35.2 kn (65.2 km/h; 40.5 mph) in shallow waters during machinery trials in 1968.[63]

- ^ "As stated in our testimony, there is current pressure to greatly reduce the defense budget, which led to the decision to retire two battleships. Because the battleships are costly to maintain (about $58 million to operate annually, according to the Navy) and difficult to man, and because of the unanswered safety and missions-related questions, the two remaining battleships seem to be top candidates for decommissioning as the United States looks for ways to scale back its forces. If the Navy also decommissions the remaining two battleships, the Navy's entire $33 million request for 16-inch ammunition could be denied, and the $4.4 million request for 5-inch/38 caliber gun ammunition could reduced by $3.6 million."[114]

- ^ The expected performance of the current rail gun design is a muzzle velocity over 5,800 m/s (19,000 ft/s), accurate enough to hit a 5 m (16 ft) target over 200 nmi (370 km; 230 mi) away while firing at 10 shots per minute.[122]

- ^ Praise for the service of these battleships includes comments from shore parties observing the battleships' bombardments during their wartime services, such as those received by New Jersey in the Korean War and the Vietnam War.[127] When reactivated in the 1980s Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union Sergey Gorshkov stated that the battleships "...are in fact the most to be feared in [America's] entire naval arsenal..." and that the Soviet's weaponry "...would bounce off or be of little effect..." against the Iowa-class battleships.[128]

- ^ Missouri had not been mothballed prior to the outbreak of the Korean War due to an executive order issued by then President Harry S. Truman.

- ^ A Government Accountability Office report on the operating cost for each individual Iowa-class battleship in 1991 reported that it cost the United States Navy $58 million to operate each individual battleship.[114]

References

[edit]- ^ Hyperwar: BB-61 USS Iowa Retrieved 1/7/23

- ^ a b Helvig 2002, p. 2

- ^ Hough 1964, pp. 214–216.

- ^ a b Sumrall 1988, p. 41.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin 1995, p. 107.

- ^ Friedman 1986, p. 307.

- ^ Conference on the Limitation of Armament, 1922. Ch II, Part 4.

- ^ Friedman 1986, pp. 307–309.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin 1995, pp. 107–110.

- ^ Friedman 1986, pp. 309, 311.

- ^ a b Burr 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Winston, George (15 September 2018). "Built To Last: Five Decades for the Iowa Class Battleship". War History Online. Timera Inc. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Friedman 1986, p. 309.

- ^ a b Friedman 1986, p. 310.

- ^ Friedman 1986, pp. 271, 307.

- ^ Friedman 1986, pp. 309–310.

- ^ a b Friedman 1986, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Friedman 1986, p. 311.